Designers have been trying to get into the mind of their players for as long as there have been games.

We want to be able to communicate ideas, inspire emotions and to drive the players to satisfying outcomes without revealing what is behind the curtain.

Last Tuesday morning at Develop at Brighton 2014, Berni Good, the founder of Cyberpsychologist Ltd, brought together a track of people dedicated to discussing the academic principles of psychology with its practical application.

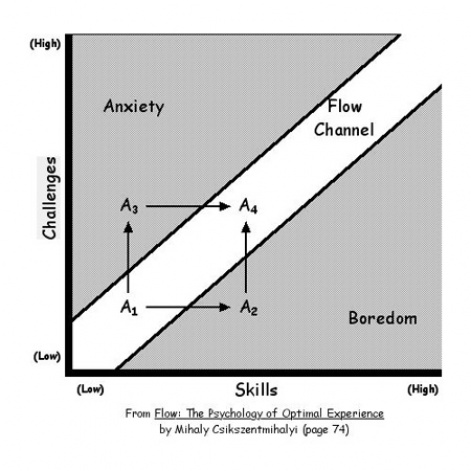

Play is a behaviour that academia has taken a lot of time to analyse. For example you may be familiar with Csikszentmihalyi's ideas about Flow; it's the mystical position of bliss which exists in the balance between frustration and boredom.

But how this affect the way we play in mobile or social games?

If it ain't got that swing

Dr Linda Kaye from Edge Hill University talked about how social context impacts the emotional experience of playing digital games and showed us how their research looked at the ways in which social flow depends on a collaborative competence - a shared sense of belonging and an awareness of the task-related skills required.

This means if we plan to make a game, we have to be aware of the relative skill of each player, or we won't retain their interest.

That doesn't mean everyone has to have exactly the same skill but any asynchronous imbalance has to be accommodated in the way the game is played. We see this in a real life. Consider the role of the handicap in golf.

Both parties are required to play at their best in order to compete with the other. However, the target number of shorts over the match for the more skilled player is lower than for their opponent. Indeed this doesn't even have to provide a perfect balance; we just need to feel we have a fighting chance.

This conveniently leads to the idea of needing to immediately understand what tasks we will be expected to perform.

Having a shared sense of belonging or social identity is also vital for social flow. It gives us a sense of purpose or common mission. Our interests are aligned and that makes it possible for us to work seamlessly together.

That idea, however, is also tied into the concept of social identity: the way we create a sense of who we are is strongly linked to the groups that we most strongly identify with.

Don't get me wrong. We can learn through experience what makes a social games tick; however, there is a difference between making our assumptions based on the way we see a game of Jenga, or perhaps the co-op missions in Call Of Duty.

The analysis of the underlying principles combined with consistent testing to prove statistical significance allows us to make better decisions without inherent bias.

The right questions in the right order

All of this is good to know but putting a little science into our game design process is, of course, more complicated than just reading the relevant papers.

At this point, we had Alex Meredith from Nottingham Trent talking about the issues of designing research methodologies.

Fundamentally we have to ask ourselves what we really want to know and how we can capture that information? We have to be careful to avoid letting our preconceptions affect the outcome.

The unfortunate wording of questions, or sometimes even just the order of the questions can influence outcome.

Thinking outside of the answer

In this way, constructing a formal project isn't unlike setting the conditions of a game.

We have to understand what variables we need to capture and how we will measure them. We then have to consider the players' behaviours and the consequences of those actions and how that might make the player feel.

Games offer a safe place where challenges can be overcome and even mastered.Oscar Clark

The trouble is we often don't fully understand the unexpected consequences of what our questions actually mean in practice; especially where we are asking players to imagine how a product or service might function.

It's often easier to look at how they use an experience you have developed for them and ask them to tell you how they feel.

Even then there is the risk that players' will provide comments just because they feel they should and that itself distorts the outcome. That risk can be minimised with good experimental rigour, as well as by having larger numbers of participants; raising the statistical significance of the results.

It's not easy. I'm not trying to put you off doing this kind of research for your game; but I do want you to be realistic about the potential pitfalls.

Making you feel all right

The track concluded with Berni talking about the latest papers related to games which have been published. The sheer scale of the material which is available for designers to learn about how players behave is staggering.

Berni explored just the tip of the iceberg, but there was clearly enough to justify at least a full day of talks. She explored the concept of the Uncanny Valley and how a recent study has identified there is a critical factor around the eyes and forehead which we associate with psychopathy if this region fails to respond 'normally'.

Similarly she talked about ideas of character attachment, player avatar identification, and character development.

In particular, she talked about social determination theory and the role of autonomy, relatedness and a sense of competence to people's well being.

Games have huge value to us as individuals because they inherently offer this kind of positive reinforcement. They offer a safe place where challenges can be overcome and even mastered; whilst the players get immediate positive feedback.

Knowing the details of how this works isn't just useful to help us design better games; it also helps us demonstrate the value of our medium to our audience.

Perhaps through this we can overcome the residual and largely untrue negative associations such as games and violence.

Oscar Clark is a consultant and evangelist for Everyplay, the free SDK that records and shares your favourite moments of play. Everyplay was acquired by Unity Technologies in March 2014.

Find out more at developer.everyplay.com

He is also author of "Games As A Service: How Free To Play Design Can Make Better Games" published by Focal Press is now available on Amazon as well as Kindle, iBooks and Kobo.

To follow Oscar on Twitter, check out @Athanateus