His practice focuses on complex patent, trademark, and copyright cases, representing a broad range of clients, from established companies to start-ups.

In the wake of two recent high-profile lawsuits involving game copycats, clones may be facing a tougher legal landscape.

The law is clear that copyright protects expression, not an underlying idea. But courts have recently appeared more receptive to arguments from copyright holders that a greater portion of the content in their games falls in the expression bucket rather than the idea bucket.

If this signals a trend, it could very well impact the pending copyright battle, Electronic Arts, Inc. v. Zynga Inc.

Early battles

By way of background, copyright fights in the video game industry are nothing new. As far back as 1982, Konami and other game developers were using copyright to protect early games from knock-offs.

Early cases were brought against clones of Pac-Man, Defender, Galaxian, Karate Champ and others. The decisions in a number of those early cases dealt with the basic question of whether or not copyright protection even applied to the audiovisual aspects of a video game.

Because copyright protection requires that a work be fixed in a tangible medium, early clones argued that the audiovisual aspects of a game as opposed to the actual code are not "fixed" but instead dependent on user interaction, thus falling outside the scope of copyright protection.

The courts rejected those early arguments and held that copyright protection does, in fact, extend to the audio visual aspects of a game.

The shift

Despite affirming the availability of copyright protection, some early cases Data East USA, Inc. v. Epyx, Inc. (Karate Champ v. World Karate Championship), for instance tended to find that the protection was relatively thin.

In part due to the limitations of the technology and the rudimentary nature of the games at issue, courts seemed to have a difficult time conceiving of copyright protection that would extend beyond the strict confines of the art and sound assets included in a game.

But more recent cases take a somewhat different approach.

In May of this year, in Tetris Holding, LLC v. XIO Interactive, LLC, a federal court in New Jersey rejected what has become a clone developer's standard defence that it copied only non-expressive, functional elements not entitled to copyright protection.

Instead, the judge largely adopted the arguments of Tetris Holdings and found the developer of a Tetris clone liable for copyright infringement for copying the look and feel of Tetris.

More recently, in Spry Fox, LLC v. LOLApps, Inc., et al., the defendants developers of Yeti Town, a clone of Spry Fox's Triple Town asked the court to throw out Spry Fox's case based on the same kind of arguments used by the defendant in Tetris.

In September, the court denied the motion to dismiss. In doing so, the court pointed to the similarity between modern video games and movies and noted that "a video game, much like a screenplay expressed in a film, also has elements of plot, theme, dialogue, mood, setting, pace and character."

Because the court held that Spry Fox had at least made a plausible showing that the defendants had copied these elements of Triple Town, it refused to throw out the case.

Shortly thereafter, the case settled, the Yeti Town intellectual property was transferred to Spry Fox, and Yeti Town was pulled from the market.

The heavyweight bout

This takes us to EA v. Zynga, a case currently winding its way through the judicial process in San Francisco.

Filed in August of this year, EA's complaint asserts that Zynga's The Ville is a blatant clone of EA's Facebook game, The Sims Social. EA argues that Zynga shamelessly copied from The Sims Social, stealing the game's character creator, homes, character bodily needs, and character interaction and socialisation, among other elements.

For anyone who has played the two games, there is no denying the striking similarity between The Ville and The Sims Social.

But that clear similarity does not necessarily mean the case is a slam dunk for EA. Rather, much of the case will come down to a fight over two copyright doctrines: merger and scènes à faire.

Under the doctrine of scènes à faire, Zynga will try to show that the content The Ville shares with The Sims Social is merely made up of stock or standard elements within the social gaming genre not entitled to copyright protection.

As an alternative, under the merger doctrine, Zynga will assert that to the extent it has taken elements from The Sims Social, those elements are required by the very nature of the games at issue in other words, the idea underlying these games has 'merged' with its expression.

For instance

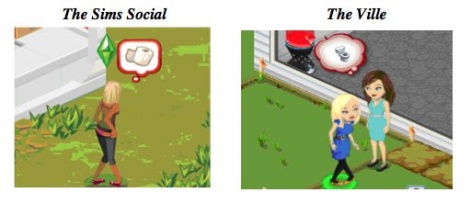

By way of example, in its complaint, EA argues that "in both games when the characters feel the need to use the toilet, they make similar uncomfortable pigeon-toed stances, " as illustrated by the following screen shots:

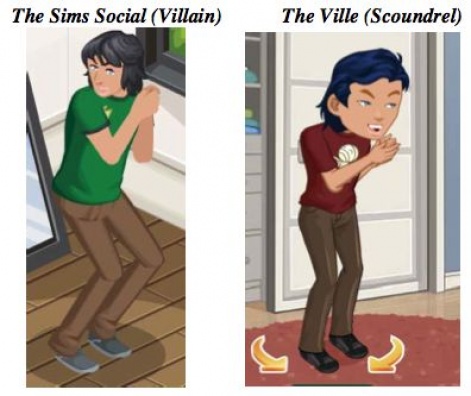

In another example, EA states that "in the animation associated with selecting the 'Villain'/'Scoundrel' personalities, the characters in both games are seen doing the same evil-scheming gesture, " as shown below:

While these elements of the game are certainly similar, Zynga will argue that these similarities are due to the fact that the pigeon-toed 'potty dance' and the scheming gesture of the evil character archetype are prime examples of scènes à faire and therefore not protected by EA's copyright.

Walled garden

EA also argues that the implementation of certain The Sims Social game mechanics are reproduced in The Ville in violation of EA's copyright.

An example of this is the 'walls down' mode, where the walls of a structure in the game are removed allowing the player to observe and access the interior.

EA argues that The Ville copies the 'walls down' mode almost identically, replicating the unique and original look of the free-floating windows and doors.

Screen shots comparing the 'walls down' modes of the games follow:

The Sims Social ('Walls Down' Mode)

The Ville ('Walls Down' Mode)

Aside from arguing that this implementation of the 'walls down' mechanic has appeared in games for years, Zynga will also argue that the only way to really implement a 'walls down' mode is to, well take the walls down.

Zynga will argue that this is a perfect example of an idea that has merged with its expression and is therefore not protected by EA's copyright.

The outcome?

Of course, with the recent news that Zynga laid off the team behind The Ville in October, the game may be nearing its final days. That would likely hasten the settlement of the pending case between EA and Zynga.

But barring a quick settlement, who would likely prevail in the EA v. Zynga battle? If looked at element by element, on particular elements, Zynga has some strong arguments regarding the doctrines of scènes à faire and merger.

However, if I were in Zynga's shoes, that would give me little comfort.

Despite having solid defences for discrete portions of its game, when looking at the total look and feel of the two games, the sheer breadth of the similarities between The Ville and The Sims Social would likely carry the day in EA's favor.

EA's complaint, spanning 36 pages and 111 paragraphs, details similarities that are so extensive and uncanny, it would make it difficult for Zynga to convince a court or a jury that it did not violate EA's copyright by stealing the look and feel of The Sims Social.

This is especially the case given the outcomes of the recent Tetris and Spry Fox cases in which many of the arguments Zynga would likely make were unsuccessful.

Different but the same

So, is the law relating to gaming and copyright evolving, and if so, does the development community have reason to be concerned about increasing limits to innovation?

The answer to that question is complicated. To be clear, technically speaking, the law has not changed. The bedrock principle of copyright law that copyright protects the expression of an idea and not the idea itself is practically untouchable.

That said, with an ever-increasing number of knock-off games, especially in the mobile arena where producing a clone can be quick and cheap, developers seem to be resorting to legal action more frequently and the courts seem to be somewhat more receptive to these cases.

What we're seeing is by no means a seismic shift in the legal landscape. The basic tenets of copyright law will not be changing any time soon. But we may be seeing a subtle but important shift in the way the courts are applying those basic tenets to video games.

As an avid gamer, my hope is that the pendulum continues to swing back in favour of greater copyright protection for games to settle at a nice happy medium that discourages outright copyists while preserving more than enough room for innovative game developers to build upon preexisting ideas.

You can also follow Jack on Twitter for regularly updated game-related IP news.

Jack also provides counsel on intellectual property portfolio management, business objectives, and strategic risk analysis.