The more I talk about the monetisation of games, the more I think about its impact on game design.

This affects every kind of game, no matter the business model, but becomes particularly important the more we consider how to make better free-to-play games.

In 2007, Clint Hocking (LucasArts, Ubisoft, now Valve) coined the term Ludonarrative Dissonance in his critique of Bioshock to describe the conflicted demands of the gameplay against the demands of the narrative.

He argued that the needs of character progression worked against the narrative structure to prevent the player from connecting with either; leaving players unsatisfied with both.

You can't please two masters

This is an important design principle, especially with narrative led games.

In a similar way, I believe it's essential to consider the impact of the business model on both narrative and gameplay.

We need to think about how we can avoid what we might call a Lucre-Ludonarrative Dissonance.

Love of money...

Of course, even the premium payment model has an impact on my gaming behaviour.

The upfront price sets an expectation of value; whether it's a $60 console title or a $1 mobile game. This instills an expectation of return and I'm motivated to get at least that value from the game.

I want to maximise the invested utility and this desire sustain me through all kinds of frustrating tutorials, game controls or mechanics. Assuming that the core game is good enough, most players will be fairly forgiving.

However, freemium games don't have this utility; at the start, we've not invested anything in the game. The game designer has to pull out all of the stops if they want players to keep playing, let alone spend any money.

The trouble is virtual goods inevitably affect the gameplay; directly or indirectly.

At the start of a game, players have little invested

Take a resource building game in which we spend in-game currency to build up our tools, environment, character etc.

If we purchase additional in-game currency, this removes the resource restriction created by relying on what we earn through play. This fundamentally changes the game.

Similarly, energy mechanics forces the player to consider each action in terms of the effort and rate at which that energy recharges.

It can create situation when the player can't play the game without buying more energy and forces them to come back later if they want to keep playing. This interrupts the flow of play, but can also create strong reasons to return to play once that energy has recharged.

This kind of dissonance is not just about the virtual goods. Advertising - e.g. a cross-promotion interstitial - set in the middle of a playing session or rather than the loading pages can also frustrate player enjoyment.

Playing a different game

At different points within the player lifecycle our attitudes to purchases may change.

As we are learning whether the game suits us and fits into our regular entertainment, we could easily be put off by the perceived 'threat' of having to spend money at all. It's also possible that we may value the option to 'buy our way' out of a restriction inherent in the free mode of play.

As we convert to being regular players, our attitudes may change, leaving us more open to spending unless the game starts to nag too much; more than that our personal objectives in the game often change over time.

The best example I can think of for this was my experience playing CSR Racing from Boss Alien/NaturalMotion.

Around the third tier of the game, I found that the core drag-race mechanic transformed from being the core gameplay to simply a mini-game which allowed me to earn money and gold faster.

Is this CSR Racing's core gameplay or just a cow-tapping mini-game?

The 'real' game for me became selecting the right upgrades and races which would get me the most income fastest and with the optimal use of fuel. Of course, I could buy more in-game money, fuel, gold or indeed better cars.

However, that would defeat the purpose I had found in playing the game and my personal narrative as I attempted to rise up the ranks to defeat the other racers. A classic example of Lucre-Ludonarrative Dissonance.

Thinking outside the wallet

Now there are designers who think the very use of virtual goods will inevitably corrupt a game and diminish its purity.

I believe the use of money-based goods can, just like a well designed narrative, benefit the gameplay, however. We just have to think about the consequences of our monetisation methods and use them as design tools.

That way we can do more than avoid Dissonance; I believe we can create a Resonance, which can make a better game.

An example of how this might work came up recently at the Game Monetisation Europe 2013 conference.

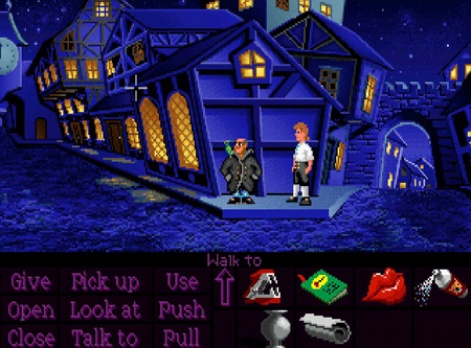

A member of the audience suggested that you could monetise a free-to-play Monkey Island-style point & click adventure by restricting the number of uses of puzzle objects.

Is there a lesson for free-to-play game designers here?

That might sound like sacrilege to the purist, but it could have a beneficial impact on how we approached the game.

What if we only had a limited number of tries per day to get Pegnose Pete to come out of his hideout, but could buy more attempts? How might that affect the way we approach the puzzle?

We might take longer to find out from the people on Lucre Island that he lost his nose to a duck. Unlike selling hints, this approach works with the flow of the game and adds a real-world consequence to getting it wrong.

It also creates a good reason not to simply resort to random clicking on the screen. You probably have to work harder to make sure the puzzles are entertaining enough to retain users.

The bottom line

Of course, this makes a different game; but whether it's a better or worse game depends on the designer.

We can use virtual goods in many different ways adding new strategies and consequences. The limit is only in our ability to recognise the value of virtual goods not just in terms of revenue but also as a design tool.

To find out what Oscar's evangelising, visit the Everyplay website.

To find out about Oscar's minute-by-minute existence, follow him on Twitter.