Sorcery! began life as a four-part gamebook series, released under the wildly popular Fighting Fantasy banner between 1983 and 1985.

Written by Steve Jackson, the series had players turning pages and rolling dice to traverse a treacherous fantasy world in pursuit of the Crown of Kings - a natty little headpiece that imbues the wearer with magical power.

In 2014, more than 30 years after the original paperback release, a Cambridge-based indie studio called Inkle launched its digital adaptation of the first Sorcery! instalment, The Shamutanti Hills, on the App Store.

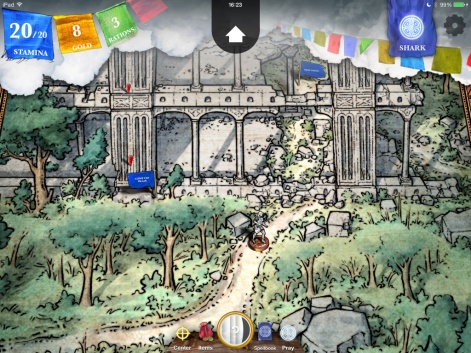

Gone was the page turning, dice-rolling, and pencilled-in notes, replaced with streamlined touchscreen movement and combat systems atop a beautiful 3D map.

And now, two years later, Inkle has finally finished its adaptation of the quadrilogy with the launch of series finale The Crown of Kings.

To learn more about the development process across the entire series, PocketGamer.biz called upon Inkle's Creative Director Jon Ingold.

PocketGamer.biz: When did the idea to adapt Steve Jackson's Sorcery! for mobile devices come about, and how was contact made with the original author?

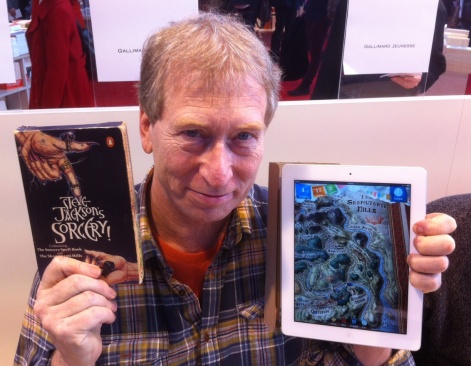

Our first contact with Steve was via another dev - Richard Evans, of Versu and The Sims fame - who knew that we were looking for collaborations and opportunities.

As a tiny team with what we felt was quite a new idea, we didn’t want to simply set off on our own IP, but instead we wanted something that would help us extend our reach quickly.

That has proved to be quite an expensive decision in the long-term, but ultimately I don’t think it was wrong - had we made our own series from the start I think we would have struggled to generate any attention.

We showed Steve an early demo of our inklebook story platform in a pub and he said “come back when you’ve sold 10,000 copies”.

So we did Frankenstein, written by Dave Morris, and when that passed the 10k mark we went back to Steve and promised him the world - a map, a strategic combat system with procedural text, a gesture-based spellcasting system, a day/night cycle.

Honestly, I think we probably said we’d make it voice-activated too.

He gave us the licence, and off we went.

To what extent were you inspired by what was going on in the digital gamebook space at the time, courtesy of Tin Man Games and other studios? How did you want to do things differently?

Our main inspiration when we founded the company was actually the Kindle and the Kindle app on iPhone, specifically.

When we started out, we weren’t intending to be a games company at all, despite our background in console development: we were going to bring interactivity and technology to the publishing industry.

We weren’t intending to be a games company... we were going to bring interactivity to the publishing industry.Jon Ingold

So our focus was “how could you make reading on an iPhone more compelling?”, and our solution was to bring in just enough narrative-focused gameplay elements to make the story feel reactive to you.

However, we pivoted: we found the games market to be a welcoming place full of new ideas, and the publishing market to be limited and conservative.

By the time we were developing Sorcery! we were already making that shift: we did our first press previews at PAX East, for instance.

We did look at other gamebook creators at the time, of course, but generally felt they were relying too heavily on the very static nature of a true gamebook - full pages of text, for instance, which weren’t very appealing to read; and large choices rather than our model of small, stacked options.

So in terms of our game design we actually looked more at parser-based interactive fiction, and its model of short interactions, a lot of back and forth between the player and the game, and a lot of multi-step actions.

We wanted the text to rewrite itself to the current context, not just on special occasions, but all the time. Our Sorcery! is ultimately a lot more Zork than Lone Wolf.

When work began on Sorcery! part 1, how big was the team? Did it grow as the series progressed?

For the first two games there were two of us; I did the writing and day-to-day game design; and Joseph did the development and graphics.

We outsourced the things that we couldn’t cover - such as character art, and the map - and a friend did the audio design.

This was originally for fun, although he later became a full-time team member, handling our Android and Steam development, and most of Sorcery! 4.

As the games got bigger, we started to look for help with the writing, and hired a contractor, Graham Robertson, for a few scenes of Part 3 - which we enjoyed so much that we brought him back for the majority of the first-pass content of Part 4.

A lot of the new material in the last game is his. If you fall in love with a Goblin or wind up worshipping a dead whale, you’ve Graham to thank.

How did you arrive at the navigation and combat systems? Did you experiment with other ways to convert the page turning and dice-rolling to touchscreen?

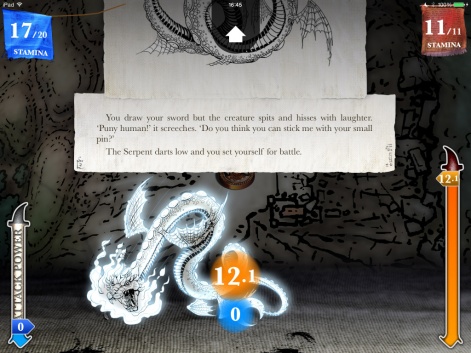

We knew from the start we didn’t want to do dice-based combat. Real dice are fun - especially for children: you can blow on them, and squeeze them, and curse them when they don’t land how you want them to.

But virtual dice always feel unfair. If you’re going to do random number work in a game, you have to hide the dice and give the player some strategic choices instead, so they feel the outcome is at least a little bit their fault - and that’s essentially what we’ve done.

The combat system in Sorcery! has been a really divisive point since we introduced it.

The combat system in Sorcery! has been a really divisive point since we introduced it.Jon Ingold

Some people really like it. It’s simple, but smart; you never quite know how it’s going to go, but if you’re paying attention you can usually best even the toughest enemies near-flawlessly.

Some people have just never "got" it, though, and find it random and counter-intuitive. I think perhaps we could have tutorialised better!

Personally, though, I’m happy that it's lasted four games and allowed us to deliver both easy fights and big bosses, and I love the balance of strategy, psychology, and flat-out risk-taking.

I love that it’s a system that’s more about thinking “how wild is an enraged Spikehawk?” than it is about adding up modifiers.

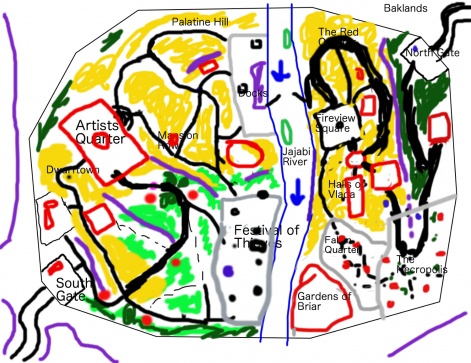

Navigation, on the other hand, was something of a discovery: we were originally thinking of simply using the map as a kind of “chapter selection” screen, but the more we tried it, the more we found that it added a great tactile layer to app.

So we made the story content of each location shorter, and simpler; we moved as many moments in the story as we could to the map; we even found it worked to add in essentially blank locations that acted as a pacing element from one place to another.

The map went from being an illustration to a game-board and took the whole game with it.

The other main part of the series is the actual story-flow itself: small pieces of paper with choices as headings, with the unchosen scraps tossed aside when your chosen scrap rolls up to join the text flow.

The whole cycle of that was very, very carefully designed and iterated on to make sure it communicated what was happening, and led your eye naturally from choice to text back to choice again.

We’ve seen a lot of choice mechanics over the years, but we felt ours was the only one that really encouraged easy, almost accidental reading of the content.

…And then we think we improved on it for 80 Days, of course!

Why did you decide to allow players to rewind and make different decisions? Did you consider a more permanent, uncompromising approach?

Gamebooks are fun - they offer a huge range of actions, and opportunities - but it’s hard to get away from the fact they are basically unfair.

Something that works in one context might kill you in another, and it’s really down to the whim of the author.

We try very hard to make sure our encounters feel engaging, balanced and entertaining - not always fair, certainly, but we try to ensure they aren’t arbitrarily unfair.

Gamebooks are fun, but it’s hard to get away from the fact they are basically unfair.Jon Ingold

But in the end, if a player has limped through the last fight with only a single stamina point, there’s not much you can do for them.

We realised pretty early on that with a game like Sorcery!, the fingers-in-the-pages approach of players wasn’t cheating, but rather a core mechanic for exploring the game, and so we were pretty certain from the start that we wanted to include it in some form.

And there’s a nice trade-off in the final design - because rewinding happens at the map layer. That means that within a story section your decisions are permanent: so we get a nice “oh no!" sensation from a choice going badly, and you having to deal with the consequences - without having to actually destroy your progress through the game to get that feeling.

And of course, a lot of our consequences are bigger than one location - so the real sadistic joy comes from the terrible thing you did halfway across the map coming back to haunt you when it’s too late to rewind.

I mean, you could rewind, of course. There’s nothing to stop you. The button is right there, waiting for you. But you’d lose all that progress, and there’s nothing worse than that…

And somehow, the player choosing to live with a difficult consequence is more powerful than them being forced to.

How much of the writing comes directly from the original texts, and how much had to be adapted? What was your approach to this?

For the first part, we followed the text quite carefully, seeking to expand on scenes in the original, and add detail, rather than inventing new encounters from scratch.

So where the book might say “you talk to the barkeeper”, we would write a short dialogue scene between you and the barkeeper, but it would cover the same basic ground.

Then Mike drew the map for the first game, and it was lovely, and enticing - and it had lots and lots of empty locations on it. So we started to fill them in. We created more paths, and more encounters.

We built alternatives for major plot points, and new ways through. And we found that we liked it. We began to relish hiding easter eggs in the stupidest places.

By Part 2, that meant we were making buildings, streets, chains of encounters that were entirely new… and so long as we made sure the new material stayed true to the spirit of the original, the joins were seamless.

The world had simply got bigger.

So as the series continued we changed from following the books towards making designs into which the books fitted: inspiring the themes and characters and storylines, but not dictating how events and spaces fitted together.

We’ve used every encounter from every book - but we frequently twist them, or reimagine them.Jon Ingold

In the end, we’ve used every encounter from every book - but we frequently twist them or reimagine them, or make them work in some new way.

And we love adding traps specifically designed to catch out people who know the books.

Back in the '80s, the books were extremely cunning and innovative, full of little tricks and puzzles that played with the gamebook form - not least the way the books of the series connected together.

So we’ve tried to continue that spirit, of doing things people might not expect.

In particular, we’ve tried to get away from the classic gamebook design of the “one true path” you discover by replay, because that doesn’t really work in a game where a replay is so slow compared to flicking through a physical book.

We’ve been aided in all this by Steve, of course, who’s given us a lot of freedom and encouragement to go away and innovate.

He’s a restless spirit, and I think he’d always rather see something new and exciting be done with his work than an uninspired recreation.

Who was responsible for the hand-drawn world map, and how important do you think it is for the overall feel of the series?

The maps are drawn by Mike Schley, an illustrator and fantasy cartographer who contacted us shortly after we announced the project - and we just loved his style.

The maps are the main touchstone for the whole experience, really, and I’ll always remember the first time we showed people the Shamutanti Hills map with the mountains raised in 3D; it was a glorious use of an iPad screen!

With each additional part we’ve given Mike more and more to do ridiculous things to do; from the individual buildings and rooftops of Kharé, to the internal structure drawings, to the two time-layers that blend seamlessly in Part 3.

In Part 4, he’s adding texturing to his list of talents, and our 3D models all have hand-drawn surfaces, as well as exterior and interior layers.

I love Mike’s work, and he’s been a fantastic collaborator, putting up with the absolute worst in sketch-maps to work from, and always producing incredible results.

We have a whole phase of the writing process dedicated to him now - “post-Mike writing”, where we take what he’s drawn and add story to explore the bits he’s added.

The series entry that introduced the most changes was the third, bringing time travel elements and a more open world feel. Was this led by the text, or a desire on your part to innovate?

It was a natural evolution for the series, really. The first game followed the gamebook structure very closely - and it made sense, as you’re just pushing forwards through the hills.

When we made the second, exploring a city, that totally linear structure didn’t make as much sense: if I’ve gone over to this side of the city, why can’t I loop back and explore the rest?

A constrained linear flow was frustrating and didn’t make enough sense when laid out on a map.Jon Ingold

So we added as much of that as we could in late-stage testing, but it was something of a hack; we were still limited by the way the game had been otherwise built.

For the third game - set in an open wasteland - we realised we needed to tackle the exploration problem from the start; so we designed every location to be flexible, so that the map could be fitted together in any order.

It was a huge internal change and it had a lot of knock-on effects - we had to change how rewind worked, for instance, since now that you revisited locations, you couldn’t simply “rewind to that place on the map”.

And we already had sleeping / day-cycle mechanics, but now time and location weren’t tied together, so we had to add a true day/night cycle.

So really, the open world design was more of a bug fix - a constrained linear flow was frustrating and didn’t make enough sense when laid out on a map.

But the third book was a great place to introduce it, because the original book for Part 3 is all about a wasteland: a lost place, a desert, the sort of place you could wander forever.

Are there any other significant changes introduced for the fourth and final part?

The biggest change for us has been adding 3D models to the map, making it more vertical.

The Citadel of Mampang isn’t flat, and there’s a fluid cut-away effect so that you can go inside towers - alongside the interior maps we’ve always had for more complex, multi-storey buildings.

All of that has taken a lot of work to get working right.

We’ve also made a big change to the gameplay, concerning the way the rewind mechanics work in the game.

You’ll have to live with the consequences of your decisions a lot more this time - but all the same time, the game is still fun-first, and we won’t go throwing your progress away in the name of “more challenge”.

Finally, from a story point of view, we’ve added a disguise mechanic, so you can dress up as different kinds of people, and it’ll change how other characters react to you throughout the citadel.

My favourite way to play is disguising yourself as a merchant, because everyone hates merchants.

What would you estimate was the total development time for each entry? How did you manage to balance development of Sorcery! and 80 Days?

The first two games took about six or seven months - in our first couple of years at Inkle we were astonishingly productive, making two or three games every year.

But Sorcery! 3 was an explosion in complexity, both on the writing side, but also on the code side too, with the tower beacons and the map layers in particular taking a lot of work to get looking right.

In our first couple of years at Inkle we were astonishingly productive, making two or three games every year.Jon Ingold

That one took just over a year. Sorcery! 4 was a tiny bit longer again, mostly on the writing side, because the game is very, very large and complex.

80 Days slotted in between parts 2 and 3 and was intended to be a side-project; something we were doing because we thought it was a good enough idea that we had to do it.

That was why we originally brought in Meg Jayanth to write it for us: the idea was to not take too many resources away from the “main crop” project, which was Sorcery!

But the more we developed 80 Days, the more complicated it became, and we were soon all in the thick of it and Sorcery!’s development stalled completely while we tried to bring 80 Days together.

That game ended up at least four times larger than planned; with scores of features that we built, changed, threw away, redesigned and so forth - but then it also did fantastically well, and the extra effort really paid off.

Sorcery! was made using your own ink1 engine. When was this developed, and how did it improve your productivity?

Ink was the very first piece of technology we built as a studio, and every project we’ve done has used it in one way or another.

As a writer, I love it - I don’t believe I can write good interactivity in any other language.

Ink is designed to get out of the way, and be good for skim-reading, editing, and redrafting. It’s a language designed to “just keeping going”, so you can write fast and fix later.

The latest version of ink - the one we’ve open-sourced - is a step-change from the original version.

It’s more robust - it’s “proper” code, this time, rather than a horrible, hacky piece of bad Perl - and it’s got more powerful features baked in.

It makes some things that are impossible in ink1 easy. I’m really enjoying getting to know it.

Did you find that a substantial number of Sorcery! players have stuck with the series as new entries are launched? Is a drop-off with each new release inevitable?

In any episodic series, you expect a drop-off, but it’s been a lot less than we’d expected.

We seem to lose about 50% of players from part to part - that’s the pattern on Android, where we don’t get many other promotional effects.

We seem to lose about 50% of players from part to part.Jon Ingold

But on iOS, Sorcery! 3 was Editor’s Choice, and so there it’s sold twice as many copies as Sorcery! 2.

Since people can start on any part they like, it’s often hard to tell who’s being retained and who’s coming in fresh.

And then, whenever we release a new part, we see a huge rise in sales of part 1. That’s the reason why the older games are still the same price as when they came out (bar the odd sale).

We’ve not been sliding the price down as the games get older - but rather saying, “if you want to play a Sorcery! game it’ll cost you the same; you pick which one you want to play”.

Some people start on 1 and work through; some have played 3, enjoyed it, and gone back to play the full series.

With this in mind, what are the unique challenges of episodic game development? Will you be doing so again, or focusing on standalone experiences like 80 Days?

The hardest part for us has simply been that Sorcery! has been going on for a long, long time.

The code is old and starting to rot; we’re stuck with design and implementation decisions from the oldest parts.

Ink has grown since then, and not everything’s built in the most sensible way. And then there’s the marketing problem - part 2 is a good game, but it wasn’t news when it was released.

So we’re more likely to do standalone experiences in future, and franchise more flexibly if we hit on something people love.

That said, I will miss the experience of making a saga. Writing the conclusion to a four part, four year series was a unique challenge and a lot of fun.

Across the entire series, which episode was the most challenging for you? Is the desire to go out on a high with part 4 a source of additional pressure?

They’ve gotten harder each time, and there’s no question about it. Part 4 was the most challenging to write.

It’s got a couple of extra mechanics which can put the game into a lot of different states, and it’s got a lot of people, and a lot of continuity in it.

Part 3 was big, and complicated, but it was possible mostly because the various places in the wastelands were separated off from one another.

Mampang is one big, busy Citadel, and if what you do in one place is forgotten in the next, it looks like a bug. So this game is a mess, but it works.

On the coding side, Part 3 was a huge undertaking - getting the two overlapping worlds to blend into each other seamlessly while also under the player’s control - was a very difficult graphic design problem, and a technical challenge.

And then there was getting it to run at a decent frame rate while still looking organic. But that’s not to say the camera work required by adding 3D models hasn’t also been difficult!

The great thing about episodic work is at least you get to bring your previous successes with you!

With the series now coming to a close, is there anything you would have done differently? What have you learned along the way?

Over the course of four games we’ve fixed and improved a lot of the things that we did wrong originally. As we build new features we tend to backport them into the earlier parts as well.

So, for instance, the game originally shipped with only a male avatar; and with a spellcasting system that told you nothing about what spell you were trying. We fixed both of those as soon as we had the chance.

Our next big project is different again, difficult in new and unexpected ways.Jon Ingold

But there’s still a list of things we never did resolve. The battle system is a little too cryptic for some players; people are often confused about which weapon they’re wielding when.

The early parts don’t handle day and night as well as the later games - I’d love to upgrade them to work on a fully open-world system, but that would basically mean a full rewrite.

Ultimately, though, we made the early games as well as we could make them. They’ve been incredibly important for the development of our company, our skills and our direction.

We’ve learned a hundred things about interactivity, about how to use choices to create tension and draw players in; we’ve also learned a lot about what not to do - in 80 Days, for instance, we moved a lot of management-style decisions out of the story and into the game layer, and it freed up the text to have more fun.

But we’re still learning. Our next big project is different again, difficult in new and unexpected ways, and it's showing no signs of getting any easier.