This article was originally published on 10 June 2013.

If history teaches us anything, it's that those who don't learn from others' mistakes are bound to share their fate.

When it comes to business, this fate is played out day-to-day in terms of share prices; market sentiment writ large in numbers.

Whichever way you play the game, no matter how smart your executives are, your impressive corporate history, or even the amount of cash in the bank, if the quarterly numbers don't add up in comparison to the competition, eventually neither does your business.

Rich upstarts

On that basis, the established gaming business is broken.

Tiny companies coming from nowhere - and in no time - have broken into a scale of earnings previously reserved for the likes of EA or Activision Blizzard.

Rovio was first but its circa $150 million in annual sales is now birdfeed compared to the $800 million fellow Finnish outfit Supercell should book in 2013.

It's probably the first company with less than 100 people to actually be worth $1 billion based on profitability rather than hype.

Japanese outfit GungHo Online isn't quite such a small concern.

Floated in on the Tokyo stock exchange and consisting of multiple divisions - a couple of hundred staff making console and mobile games - it's nevertheless one single mobile title Puzzle & Dragons that now sees the company with a market capitalisation higher the Nintendo; the industry's blue-chip share for the past 30 years - that's $15 billion.

Depending on your point of view, it was the best of times. It was the worst of times...

A hard road

In the shadow of this disruption, the companies who built the industry over the past 20 years, companies such as Sony, Microsoft, EA, Take-Two, Capcom, Namco Bandai, Konami etc, are scrambling to adapt.

Some are handling it better than others.

Of course, mobile disruption isn't the only thing many of them are dealing with.

It's part of the wider shift from a packaged goods retailer-lead business to one centered on global, free-to-play, digital distribution. But given the scale of its current hardware transition, mobile is the cutting edge of this change.

Just ask Zynga.

Not for want of trying

Still, the problem for most companies is they've been trying to deal with this shift for years.

(In the west, Activision Blizzard remains the only publisher still not to have a credible mobile strategy, but that's another article entirely.)

From the $680 million EA spent in late 2005 to buy JAMDAT and create EA Mobile, these attempts have been expensive, while their success remains arguable.

Even in Japan, which has been generating hundreds of millions of dollars annually in mobile content revenue since DoCoMo kicked off its i-mode platform in 1999, game publishers haven't been able to address the opportunity as effectively as they would have like.

Konami and Capcom have perhaps performed best, but it's been the rise of gaming networks like DeNA's Mobage and GREE that's been the key disruption.

They are the ones who have come from nowhere to record billion-dollar annual sales.

All that's happened is the game publishers have swapped their subservient relationship with console format holders like Sony and Nintendo for a similar servants-and-masters gig with their new mobile overlords.

They're already doing it again with the like of LINE and KakaoTalk.

But, you're probably thinking, 'that's 500 long words before you even start addressing the headline, Jon'.

Time for another history lesson.

A slipping down life

Back when Microsoft only cared about PC games (and that only slightly), the console world was a battle between Sony, Nintendo and Sega.

Sega was always the weakest of the three Japanese companies, neither having Sony's corporate depth or Nintendo's reputation for game quality.

What killed the company as a going hardware concern was a complex interactions of events, but in the public's mind it was underlined by the headline that EA wasn't going to support its Dreamcast console.

The eventual result was Sega stopped making hardware and games for that hardware, and switched to just making games.

In the end, it didn't have a choice. Market forces made the decision for it.

History repeating

Interestingly, EA recently made a similar pronouncement about Wii-U; another sign o' the times.

And, Wii-U aside, what the new consoles from Sony and Microsoft demonstrate is that gaming hardware per se has never mattered less.

Gamers are up in arms that Microsoft in particular appears to have led its PR assault for Xbox One not by talking about games, by rather discuss entertainment services.

It's a similar case with the changes to terms and conditions concerning how often consoles need to connect to a server, and issues arising from game ownership versus rental.

But these are actually universal changes being forced on the industry by the rise of free-to-play gaming and games as a service: something reinforced by the rise of the unconsoles from Ouya, GameStick and BlueStacks; companies that didn't even exist 12 months ago.

And the most striking fact is that for the first time, some next-gen console launch titles will also be released for the past generation of consoles.

Indeed, you could argue the PS Vita and 3DS were the last of a generation of dedicated gaming consoles, albeit portable ones.

Neither has performed as expected, and demonstrably worse than their predecessors, both in terms of support from developers and public demand.

This is the state of the industry. Only one company stands against the flux.

Lighthouse or shipwreck?

So let's get one thing straight.

With annual sales of $6.4 billion (of which $2.4 billion was software, just 3 percent from digitally distribution in 2012), and over $10 billion of cash in the bank, Nintendo isn't going away anytime soon.

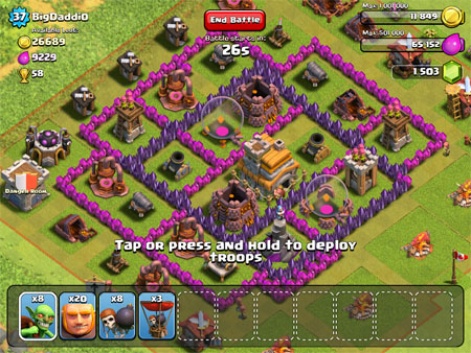

It may not have the most profitable IP any more - cf Call of Duty, Puzzle & Dragons, Clash of Clans, Candy Crush Saga, FIFA, Angry Birds - but there's no question that historically it has the most valuable IP.

Every bar-room debate about Nintendo starts "Can you imagine Mario on iPhone?".

If Nintendo decided to make games for smartphones and tablets, it would generate hundreds of millions of dollars.

You could even argue (less strongly because of the more difficult business model) that a 'Nintendophone' would be popular, if not financially successful.

But, as CEO Satoru Iwata has stated many times, Nintendo will not make games for other people's hardware, including for phones.

A smart man, and an Apple fan who was an early adopter of the iPhone, Iwata understands the battlelines.

He also understands Nintendo's longevity in the market is predicated on the fact it doesn't rely on any other company. It makes games for its gaming hardware because that's the only way it can make the best games.

The Nintendo Seal of Quality is a marketing ploy but there's truth behind it too.

And as a game developer before becoming an executive, Iwata truly believes that a game's quality is the most important reason for its success, and - in turn - this is the bedrock for Nintendo's continuing position in the gaming industry.

A thoughtful aside

In this context, let's play a little rhetorical thought experiment. Let's call it 'What would Iwata do?'

- 1. Would Iwata ever release a Nintendo game for PlayStation?

- 2. Would Iwata rush out a Mario game to hit Nintendo's quarterly sales predictions?

- 3. Would Iwata punch an investor asking difficult questions in a shareholders' meeting?

- 4. Would Iwata release a payment system whereby children could use their parents' credit cards to make $99 virtual goods purchases?

- 5. Would Iwata sanction Nintendo making a free-to-play game?

The first four questions answer themselves, but the fifth is much more interesting and cuts to the core of Nintendo's current situation.

Sure, games such as Puzzle & Dragons and Clash of Clans will generate billions of dollars of revenue during 2013. Depending on who you talk to, the global market for mobile games, mainly F2P, was around $6 billion in 2012.

So even if Nintendo made a successful phone (or released iPhone games), if it didn't also make free-to-play games, the vast majority of the money currently being made in the market wouldn't be available to it.

Hence - considered through Iwata's eyes - the mobile gaming opportunity isn't how big a slice could it take from a say-$10 billion sector, but some fraction of an at-most one billion dollar paid mobile games market.

Stacked up against the $6 billion it makes in annual sales, that's not so much of an opportunity.

Lost generation

Yet, the issue for Nintendo, and Iwata, is this current logical argument doesn't take into account longevity; something that's Nintendo.

A generation of kids (sometimes more babies than kids) are growing up with an iPad or a.n.other tablet as their plaything.

Nintendo and Mario may still have strong resonance for their parents, but Nintendo has always owned the sub-teen market. If that's slipping away, the decade following the decade following the release of the iPad is going to be a very difficult time.

Of course, the answer from every other game company CEO would be 'Who cares?'.

They have enough pain in their lives thinking about the next quarter. Just ask Mark Pincus.

Although Nintendo is not Zynga, Nintendo's compliant shareholders are not going to be inactive forever. The company's share price has remained remarkably firm - albeit down 85 percent from its 2007 high - and it now pays a dividend, so there won't be a revolt any time soon.

The sticking point

But shareholders invest their money in the place they think it will generate the most return.

Shareholders, even compliant Japanese shareholders, don't like missing out on $10 billion opportunities in a core market because a CEO has a certain way of working.

And let's be clear about this, too: Nintendo likely could make the best free-to-play games on mobile. Unlike almost every other game company, the reason it won't is moral, not technical.

That's admirable, but morality has a slippery grip when it comes to business.

Like morality, confidence is also a slippery thing, and CEOs - even Nintendo CEOs - are replaceable.

So the dilemma for Satoru Iwata is if he really believes Nintendo is better off not making free-to-play games, or mobile games, he needs to demonstrate how Nintendo doesn't lose out from not entering the fastest-growing gaming sector.

He's a smart guy, and there are other opportunities for Nintendo, especially when you have $10 billion in the bank.

But doing nothing is not an option; unless you want to follow the route of Sega, because eventually market forces are bigger than any one man or any company history.