Torulf Jernström is CEO of Finnish developer Tribeflame.

His blog is Pocket Philosopher.

Free-to-play is a more honest business model than the traditional premium model. And that has consequences for how you market.

WHAT??

Let me explain!

With the traditional pay-up-front premium model of selling games, the game company or publisher has an incentive to build up expectations before the launch.

They need to make people desire their product. It's all about the customer expectation.

What happens after the customer bought the game is less relevant. If they never even play the game, or test it only once, that's fine. They already paid for it.

I do this myself all the time with Humble Bundle games. I like to think of myself as a person who has the sophisticated taste to enjoy a fine indie game in my spare time. The problem is that I do not have spare time.

So I end up buying the games, but never playing them. Which, as I pointed out, is just fine for the indie developers. They got paid for building up the expectations.

Total excitement demanded

Free-to-play is wildly different. The clue is in the name. A good F2P game will let you play the game for free forever.

It is better to keep you playing for free than having you not play at all. You might, after all, tell your friends about it, and they might tell a friend who tells a friend who ends up paying.

Since you can play for free for several months, before eventually deciding to pay, the players know exactly what they are paying for. And therefore, expectation building ahead of a game launch is much less relevant.

A way to think about F2P is that we are giving the player unlimited try-before-you-buy.

A way to think about F2P is that we are giving the player unlimited try-before-you-buy.

We don't optimise for expectations up front, we optimise for retention of the players who ended up trying our game. If we can keep them, they will slowly spread the game to friends, who spread it to more friends and eventually we end up making money.

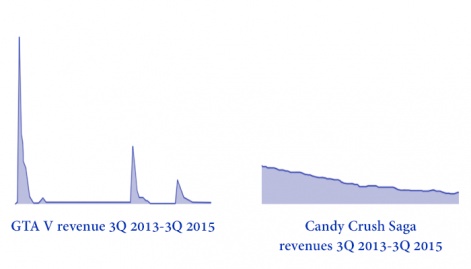

Have a look at the resulting revenue curves for successful games in both models to see the difference.

GTA V and Fallout 4 both made a lot of money in their first week. After that, the sales numbers quickly drop.

Candy Crush Saga and Clash of Clans are the opposite. They have made similar money over the games' lifetimes, but it is much more spread out in time.

I looked at the public sales data for GTA V and Candy Crush Saga, and sketched out roughly how their sales were distributed.

The curves here show how both GTA V and Candy Crush Saga made about $3 billion in the last 2 years. As far as I can tell from public data, they should be very close to each other in terms of total revenue generated over the last 2 years.

That leaves out the original ramp-up of Candy Crush Saga, of course (it was released in April 2012, about 1.5 years before the start of this data series).

While the totals are about the same, the distribution in time is very different. GTA has peaks at original launch, and when ported to new platforms (Xbox One/PS4, and PC). Candy Crush Saga, on the other hand, is very stable.

Upfront buzz

If you want the premium curve of high expectations leading to quick revenue at release, you need to do traditional marketing: creative stuff; buzz building; talking to press etc.

A good game will certainly be needed to convince people that you are worth the buzz, but what's a good game will be decided by press and early players in a matter of days.

Free-to-play marketing is different. Just about everything you do is measurable.

In this mode, you have a lot of activity based on best practises, but they are hard to measure exactly. How much did that magazine interview do to help you? Was it more or less effective than that huge poster at Gamescom? It's hard to know, but that is marketing. A traditional saying is "I know half my ads aren't working, but I don't know which half!"

Free-to-play marketing is different. Just about everything you do is measurable. You have different ads and measure click-through rates on them to optimise. You try different channels and measure cost-per-install on each.

And most of all, it's not about a huge effort concentrated around the launch date, but about a long-term process that can run over several years.

Market engineering

My friend Thorbjörn Warin who has been at Wooga, Grand Cru Games and AdColony had a nice way of saying it. You market premium games, but F2P is not really marketing - it's market engineering.

If you're an indie developer working on a new title for Steam, you want to do marketing. The guerilla kind, but anyway. You speak to game media, you're active on discussion forums, you try to attract Youtubers, etc.

If you're doing mobile F2P, you might as well not bother with that. Our Benji Bananas game gets tens of thousands of downloads every day. A news article about the game usually has such a small effect that we cannot even see it when looking at the download charts.

The chart below show tens of millions of downloads for Benji over the last 2 years (the drop in April is just missing data on Appannie). This is market engineering territory.

Ironically, at the very highest levels of user acquisition budgets, you're back from market-engineering to marketing. Just look at the TV ads of King, or Supercell's Superbowl ad.

At their level, they have maxed out what they can get from ads in other mobile apps.

Who hasn't already seen several ads for the top-3 grossing games (Candy Crush Saga, Clash of Clans, Game of War)?

That means that they need to bring in fresh users to the ecosystem rather than take users from other mobile games.

But, if you're the guys making these TV ads, I don't think you need my advice for how to do user acquisition for mobile games anyway.