To many, mobile and arcade gaming are so distinct they may as well be entirely different media.

In this case we are talking about real arcades; those increasingly rare physical spaces where the games industry itself was first forged – neon-lit places where players push coins through slots and chase high scores.

Certainly, arcade and mobile sit at opposite ends of the portability spectrum, but the most interesting distinction comes in how they are perceived.

Arcade gameplay is still generally seen as the peak of game design purity, with the players that stand at a cabinet, stick in hand, deemed to be perhaps the most devoted, most hardcore and – significantly – most authentic players.

Mobile, meanwhile, is a place still haunted by the ghost of the 'casual' movement. You don't have to go far to find somebody who will tell you mobile games are throwaway, financially manipulative and not of concern to 'real gamers', whatever they might be.

Captivating audiences

In reality, the division bears little scrutiny. Both forms strive to captivate vast and diverse audiences, using accessible gameplay that can be picked up without reams of written instruction or learning. The original Pong cabinet bore the engraved message 'avoid missing ball for high score'.

It's the kind of tutorial simplicity mobile game designers should greatly admire.

The most valuable – and perhaps least recognised – comparison to be made, however, is around monetisation. It would be inaccurate to claim that arcade coin-op is a true 'microtransactions' model, but still, arcade gamers digest content by paying in modest amounts.

Coin-op is neither free-to-play nor in-app purchase – a few edge case releases aside – but the arcade monetisation model is the foundation for so much of what gives cabinet-based games their credibility. Mobile gaming, meanwhile, rarely enjoys such an association. We've all heard the creative elite cry out 'F2P is the death of quality game design'.

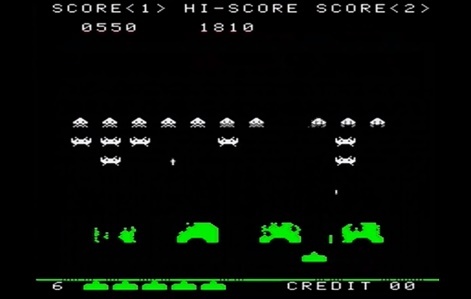

So how does the coin, credit and continue structure serve arcade game design so well? Consider the 2D shooter genre; one thrust into the mainstream consciousness by icons like Asteroids and Space Invaders, and continued for decades by cult outfits like Moss and Cave, before becoming a darling of the contemporary indie scene.

2D shooters – or shmups, as they have become known – are predominantly about scoring. Leaderboard position is everything to their players. And they are competitive with good business reason.

Players that strive for improvement and high scores come back and put more coins through slots. The best players, then, will want to beat a game on just one credit – known in the arcade community as achieving a '1CC'. With a single coin in, the best players could play through a whole game without paying a penny more.

Once they had done that, though, the battle became one of getting as much score from a single credit play-through as possible. That meant that for games to be successful, they had to offer more for the players; more nuance to scoring systems, more secrets, more capacity for player strategies and flare.

For games to be successful, they had to offer more for the players; more nuance to scoring systems, more secrets, more capacity for player strategies and flare.

Those factors would assure an arcade release commercial success. There had to be reasons to come back over and over.

Finding the fun

As Atari co-founder Nolan Bushnell famously put it in 1971: "all the best games are easy to learn and difficult to master. They should reward the first quarter and the hundredth."

The same could be applied to numerous other arcade genres and titles, from Time Crisis to Pac-Man via Donkey Kong and even the multiplayer arena of the beat 'em-up.

Over in mobile, meanwhile, the relationship between gameplay design quality and monetisation method at best has an image problem. Which brings about a question; can't more be learned from funding the original video game form?

It seems the answer is yes, and a band of gameplay-focused mobile studios have been pondering the challenge for some time.

Marek Wyszynski is the VP and co-founder of Infinite Dreams, the Polish studio behind the Sky Force shmup series, which presently thrives on mobile as two free titles, and carefully blends traditional and contemporary monetisation and game design to great effect.

It is worth noting that Infinite Dreams first took Sky Force to mobile in 2004, so they've have plenty of time to mull over how much a mobile game should mimic the arcade model.

"I think that current monetisation strategies influence the game design in a big way," Wyszynski suggests.

"You can see how certain types of games have dominated the charts completely. The idea of letting the player to spend thousands of dollars on one title is very compelling, and as a consequence the games are frequently designed around the monetisation, not the other way around."

Quality examples of some genres, he argues, are now almost non-existent on mobile, simply because nobody has conceived of a workable monetisation strategy for them. And many of those are classic arcade forms.

Yet Wyszynski concedes that the old 'pay-per-play' arcade model is rarely suitable today.

"We’ve faced this challenge with Sky Force," he admits. "We definitely wanted to recreate the same sense of excitement that we had playing the old shoot ’em-ups on the cabinets, while we were aware that we need to make the game fit into current monetisation trends.

We’ve decided that we really want to have a limited number of levels that can be replayed many times to be eventually mastered by the player.Marek Wyszynski

"So a lot of design decisions had to be made. We’ve decided that we really want to have a limited number of levels that can be replayed many times to be eventually mastered by the player – just like in the old times.

"On the other hand we knew that we have to introduce in-game currency and upgrades of the ships so that the player can feel the progress and replay the game multiple times."

Insert credit

For Wyszynski and his team, then, it became about recognising the differences. Mobile games are not anchored to a location, a time frame or a physical currency. Considering those differences carefully let the team design the gameplay and commercial system as one.

The recent Sky Force Reloaded has a diverse monetisation structure that lets players convert cash into in-game currency, which can in turn be spent on many things, from individual credits – just like back in the day – to accelerating power ups.

Importantly, though, on the whole the limitations to player progress are about skill and not monetisation. Play more, get better, and higher scores can be achieved while putting a minimum spend into the game.

As with real arcade gaming, Sky Force Reloaded's monetisation model – while nothing revolutionarily different – is coupled with the game in a way that allows both the game design and player experience to flourish.

Over at UK studio State of Play, they took a rather different approach when building their visually delicious mobile pinball game INKS. Pinball, of course, is a coin-operated amusement that predates electronic gaming, and it presented State of Play with a distinct opportunity.

As with Sky Force, it was identifying the differences between arcade and mobile monetisation that let the team build a successful game that captured much of the authenticity of its source medium, without digitally aping coin-op monetisation.

"It seems like the link [between arcade and mobile] has been broken to me, with people not willing to repeatedly ‘put in coins’ to mobile games to play it repeatedly," offers Luke Whittaker, Co-founder and Lead Designer at State of Play.

"Perhaps the mechanic might have taken hold, but as soon as companies realised they could make money by other means within IAPs, and that these were more profitable, paying to play each time wasn’t going to work. And then when these games were free, perceived value of mobile games fell and people came to expect a lot for free."

He continues: "I think it does mean there’s untapped potential and that the tension that arcade games bring to the gameplay is something we can learn from.

There’s untapped potential and that the tension that arcade games bring to the gameplay is something we can learn from.Luke Whittaker

"In INKS, which is based on pinball, we tapped into that, giving people a gold ball to start with, then a silver if they lose it, then bronze, then black. It gives you that same ‘edge of your seat’ feeling you used to get from the fact that you’d lose a pound if you lost a ball."

Under pressure

Arcade gameplay's dramatic tension – and the pressure having paid for a single coin brings – can be both a positive and a negative, however.

"Personally I find real pinball too stressful and expensive due to this ‘£1 for three balls’ mechanic," Whittaker admits.

"Too much is at stake and the game is too hard – and it’s a vicious circle I can never afford to get good at it. That was what we tried to solve with INKS, and one reason we made the game - we thought that the arcade monetisation system was actually preventing people from enjoying the game.

"We wanted to show the pleasure in the skill of the mechanic, taking the stress away just enough."

As such, INKS is a premium purchase, with additional level packs for sale as IAPs. And then there are credits available. Those credits are not used in the traditional sense, but rather to allow players to activate brief power ups such as temporary slow motion, enabling them to best a trying table.

And just like arcade credits, they are valuable, and as such offer the gameplay much; both the chance to enjoy the ego-boost of not needing them and the tension of deciding when it's time to let a precious INKS credit go.

Certainly, studios tackling traditional arcade gameplay forms are finding that a measured approach to innovating monetisation works best.

'Respect the present; remember the past' might be the rule of thumb here. And it's an evolution progressing in tandem with a change in perception of mobile monetisation, believes Damir Slogar, CEO at Big Blue Bubble, which has recently released its Home Arcade mobile game.

"Perception is slowly moving in a positive direction," he states. "I emphasise slowly, though. There is nothing significantly different that consumers didn't already experience in the arcades or with retail games.

"I have been developing and playing games for over three decades now and I bought thousands of games that I never finished for one of two reasons; either I got bored by the game or the game became too hard at some point so I gave up."

Something old, something new

Which brings us back to the only true founding rule of mobile game success: make a good, fair game.

The one major difference I see is that people saw going to arcades as a real event; one they’d make time for.Luke Whittaker

"I think we are now waiting for something new," adds Wyszynski, turning the conversation to the future.

"On one hand people are getting fed up of playing the same games – based on current F2P trends – over and over again. On the other hand, publishers will not give up the idea of monetising one player multiple times.

"The subscription model is something that could potentially enable creative freedom and maintain a high revenue stream for publishers. Are we heading in this direction? I think it’s too early to say."

It does seem that monetisation is changing, and it is those that are considering and adapting conventions born in the arcades of the 1970s that are doing some of the best work in evolving gameplay and monetisation, not just together, but as one.

Ultimately, putting a price on games comes down to one thing; value. And there, concludes Whittaker, is something else to consider about coin-op.

"The one major difference I see is that people saw going to arcades as a real event; one they’d make time for, which they’d therefore be willing to pay for," he says. "Free-to-play mobile games are often, to generalise, designed to be played anytime and for you not to make so much conscious investment.

"So it’s a task to make sure that people see your game as something of value, make it an event to play it, to make it something people will want to invest their time and money in."

It turns out that embracing arcade monetisation is 'easy to learn, hard to master'.