When ambitious South Korean mobile games outfit Netmarble (KRX:251270) starting selling its shares on the Seoul stock exchange, the headlines were ecstatic.

The second biggest ever listing in the country, the move valued Netmarble at $12 billion, raising $2.3 billion in new cash for further global expansion.

Yet two weeks on, commentators are more circumspect.

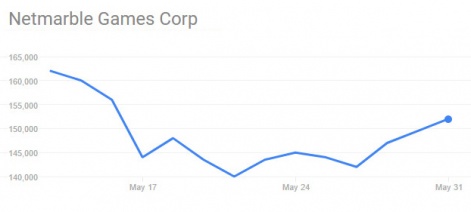

Having risen on day one, Netmarble’s share price is down 3%, and at one stage was down 10%.

Early days for sure, but could Netmarble turn out to be another example of how not to float a games company?

Show me the money

In theory, a company’s initial public offering (IPO) is a very simple operation.

It’s the first time a previously private company’s shares are made available for the general public to buy (and sell).

All companies, no matter how large or small, always have shares, of course.

As startups, these shares are typically owned by the co-founders, although as a company grows, new shares are often created so the company can raise external investment and/or reward their staff.

An IPO is the process of extending company ownership to potentially everyone.

In that sense, an IPO is merely the process of extending this ownership to potentially everyone rather than keeping it within a closed group. The advantage for the company is it gets a large injection of money, either to invest for future growth, pay off debts and/or enable co-founders, staff and previous investors to cash out.

The advantage for new shareholders is they have the opportunity to invest in what - hopefully - will be a fast-growing business. This means they expect the price of the shares they buy when a company IPOs will rise.

And this expectation is the reason managing an IPO is anything but simple.

Give or take?

Whenever a company IPOs, the headlines always talk about how much money it’s raising i.e. the number of shares it’s selling multiplied by the launch price of the stock.

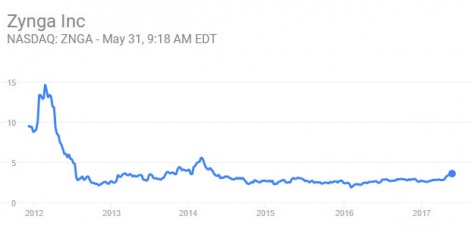

Looking back at some infamous game company IPOs, in December 2011 Zynga (NASDAQ: ZNGA) IPOed at $10 raising $1 billion. The share price had risen to $14.69 by March 2012 but then quickly fell to under $3.

Five years later, it remains under $4.

Similarly, King IPOed in March 2014 at $22.50, raising $325 million, but the priced dropped to $20.50 on day one.

By October, the shares had lost 50% of their value. Understandably, some investors were annoyed but many were relieved when Activision Blizzard offered them $18 per share to buy the company 20 months later.

The reason setting the launch price for an IPO is difficult is it’s all about the money.

The reason setting the launch price for an IPO is difficult is it’s all about the money; the money the company wants to raise versus the money investors want to make and the eventual compromise between the two.

Priced too low, investors are likely to quickly sell their shares when they rise, banking money the company which is IPOing could have received if the launch price had been higher.

Obviously, the higher the launch price for its shares, the more money the company generated from its IPO.

But, if priced too high - to maximise the return to the company and its shareholders - investors may consider the company to be overvalued and hence the share price will fall below the launch price.

This is fatal for investor confidence and all the goodwill and momentum an IPO creates immediately evaporates.

In the aftermath of a share dropping below its launch price - or ‘going underwater’ in investor speak - it’s very difficult to build it back up, potentially labelling a company as a failure for years to come.

How to price uncertainty

This pricing uncertainty isn’t helped by the timing of an IPO in terms of a company’s business cycle.

Companies which IPO are typically growing fast, sometimes very fast, and this makes them difficult to value.

In that sense, the IPO is the point at which the internal valuation of the company by its co-founders and investors collides with the view of the wider investment market. As we’ve seen, the results can be very messy.

Revenue growth can’t continue forever, of course, so companies considering IPO ensure they can demonstrate maximum growth in the period before they IPO, because their ‘growth story’ is what investors care most about.

In the case of Netmarble’s IPO, the growth story was underlined by the news its game Lineage II had generated almost $180 million during its first month; an enormous amount of money.

What Netmarble wasn’t so open about was the subsequent - and expected - decline in sales in the following months.

Lineage II remains the top grossing game in South Korea, but as other commentators have pointed out, it’s unlikely to generate $1 billion in 2017 that Netmarble suggested.

Yet this number has become a psychological anchor point for some investors, who now have unreasonable expectations for Netmarble’s future growth.

Higher, higher

To try and overcome this uncertainty about future growth and hence company valuation, the IPO process sets out a higher and lower share price range for launch.

Hence, before the company actually IPOs, it negotiates with its underwriters and other financial institutions who promise to buy the shares if public investors don’t, in terms of how it should price its shares at launch.

The aftermath of an IPO shouldn’t be the time to worry about turning the situation around.

In the case of Netmarble, the range was between 121,000 and 157,000 Korean won - an enormous spread, which highlighted the level of pricing uncertainty rather than reducing it - with the top of the range price winning out.

With two weeks of hindsight this 157,000 won launch level is looking too high, just as Zynga’s $10 (also at the top of its $8.50 to $10 range) and King’s $22.50 (the midpoint of its $21 to $24 range) proved to be.

Good examples

Of course, Netmarble can still turn the situation around, and if nothing else, it has raised over $2 billion to invest in future growth.

Similarly, Zynga shares may still be underwater but the $1 billion its IPO raised six years ago continues provided the cash it requires to try to get back to profitability.

But the aftermath of an IPO shouldn’t be the time to worry about turning the situation around, and it’s worth pointing out games companies who have demonstrated how to do it properly.

Much more modest in terms of the numbers involved, nevertheless Swedish game outfit Paradox (PDX) IPOed at €33 a share a year ago raising $60 million. Its share price has since doubled.

Meanwhile Finnish mobile developer Next Games (NXTGMS) raised $37 million when it launched at the top of its €7.50 to €7.90 IPO range in March 2017, where its share price remains.

These are the examples for US mobile developer Jam City to reflect on as it considers an IPO later in 2017, not Netmarble - which ironically - is already a major Jam City shareholder thanks to a $130 million investment made in 2015.

And as for potential investors in any Jam City IPO, consider yourselves forewarned.