At some point in their lives, most people have imagined what it might be like to float through space.

Even with the horror of Gravity still fresh in our minds, there's an undeniable appeal to watching the blue sphere we call home shrinking away in the distance as you float into the unknown. It's a feeling Michael Peiffert knows too well.

Peiffert is a graphics arts graduate who's been working in digital communications as a creative director for the last 12 years. Dreaming of working in videogames development, Peiffert designed online user experiences for companies like Peugeot and Cartier, always looking to videogames for inspiration for his work.

Then, one day he decided to stop dreaming of the stars and instead he started building a rocket.

Reach for the stars

"I eventually came to a point where I couldn't resist making games any more," Peiffert tells us. "I left Paris and its crazy lifestyle and settled in the countryside of Lyon with my wife and my newborn daughter." That's when Mi-Clos Studio was born.

"I had two years worth of salary saved, so I started to learn programming," recalls Peiffert. "Once I managed to make a character jumping on a block, I was hooked. With my friend Pulcomayo - Mind Candy's main character designer - we created Space Disorder, my first 'real' game."

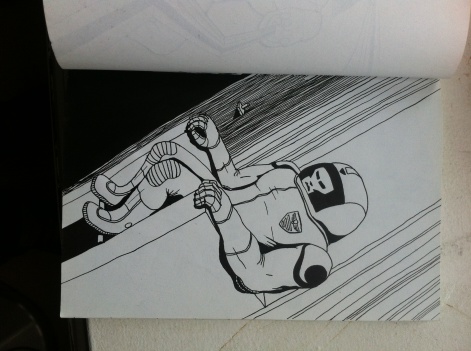

It's no coincidence that Space Disorder starred an astronaut, either. "I've been inking many sketchbooks with my spacey reveries for years," says Peiffert.

Even the portrait visible on Out There's main screen was created long before Space Disorder, but the concept Peiffert had for a lonely astronaut was just that, a concept. Peiffert had no idea how best to make it into a game.

Luckily Peiffert met someone who could help. "I met FibreTigre, a french interactive fiction author and game designer," Peiffert tells us. "He brought in his huge sci-fi literacy and clever system design to the project. Our skills were complementary, and it was just perfect."

The team spent just over a year working on the game before it was complete. "Fibre produced game design documents and wrote all the adventure in French and even translated them to English," recalls Peiffert.

The game's story is all told through text in a 'choose your own adventure' style, and Peiffert suggests there's enough text to fill a Fighting Fantasy book. FibreTigre worked on that, whilst Peiffert himself took charge of technical development, graphics and UI design.

I eventually came to a point where I couldn't resist making games any more.Michael Peiffert

"As Mi-Clos Studio's head, my role was to set up the business and marketing plans as well," Peiffert says.

"Siddhartha Barnhoorn, who had previously worked on Antichamber, composed the music and designed all the sound effects, Gaelkka improved Fibre's English translations, and Aurelien Defossez - from newly-founded French indie studio Tabemasu - helped me out on the most difficult parts of the code, which were a piece of cake for him."

With such a small team, Mi-Clos could concentrate on Peiffert's original vision and remain focused. "When I look at the first design documents FibreTigre did, you would be surprised how close it is to the final game," Peiffert reveals. "We had a strong concept and we stuck to it."

That's not to say everything made it in. Out There has faced many a comparison to FTL, but there's one big difference: the combat, or lack of it - it's FTL for pacifists.

Star wars?

"I wanted to have some sort of combat during the game," says Peiffert. "But Fibre insisted to leave [combat] out and focus on decision-making and resource management." Peiffert admits he was sceptical about the lack of combat at first, but its exclusion suited the lonely atmosphere the pair wanted to craft.

"It was a ballsy approach, but I approved the decision as it would be a strong point to differentiate our title from the never-ending stream of space games," Peiffert admits.

After settling on the concept, it was time to make the rest of the systems feed into that feeling of being a lonesome astronaut, isolated from humanity. Many of the design decisions were based around giving the game this feel.

"An astronaut has to live in a cramped space, hence the space [inventory] management game," says Peiffert. "An astronaut has more trouble to find fuel than oxygen, which can be recycled; an astronaut has to think more about his survival than going somewhere."

It's in balancing these where the game would either succeed, or get sucked out of a blast door.

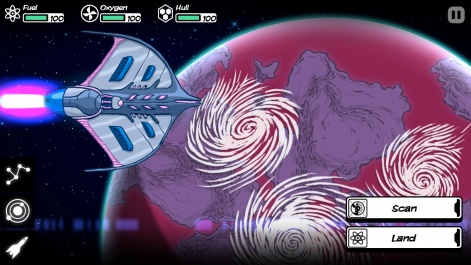

"There are many elements to take into account," remembers Peiffert. "But at the core of the game, you have the classic rock, paper, scissors gameplay: you have three critical resources to manage - fuel, oxygen and hull - and each time you try to gather materials to replenish one of them you consume the two other ones.

"The game looks brutal in the first plays, but you get farther and farther at each play."

Layered over the top of this rock, paper, shuttle balancing, there was also an element of randomness added in to make each attempt feel fresh. Of course, Mi-Clos still needed to keep balance at the fore of its agenda.

The game looks brutal in the first plays, but you get farther and farther at each play.Michael Peiffert

"We made sure that the routine - getting vital resources to survive - would not be completely random," says Peiffert. "If you plan ahead your moves, there is no way you can die. This is an exercise of discipline that asks the player to always think before acting. Then we added random events and encounters to spice things up.

"This is where it's getting interesting because you can end up in difficult situations. Each time you overcome such situations, it's very rewarding. But sometimes you die pretty brutally and we are OK with that. It makes sense with the story and the reality of being 'out there'."

Phone home

One of these random elements will see the player landing on habitable planets and conversing with the local fauna. The player doesn't understand what the aliens are saying, but each encounter teaches them a new word in the new language - a language created specifically for the game.

"First we studied how alien languages were created," recalls Peiffert. "Star Wars' Ewok language was based on Tagalog, for example. We isolated alien structures, such as composed names 'NASHAK-NAMOD' or uses of special strings of letters. We created a long DNA string of arranged letters and our dictionary dives into it in the beginning of the game to fill itself."

The alien language adds a layer of mystery to the game, as do the random events - it all adds to the feeling this is an unexplored universe. When crafting a universe, as space is infinite, it's best you can't see its edge.

"A game world works better if the player can't see its boundaries," says Peiffert. "Even if the content is huge, the narrative of Out There is much bigger than what you'll ever encounter in the game. I believe that was a key point to make the player feels [they're] part of this mysterious universe.

"What makes Out There's universe even bigger, is that it relies heavily on the player's imagination. Many things are half-revealed or suggested and reinforce this feeling of a deep narrative background."

The universe was expanded with text then, instead of making it visually vast. Mi-Clos made Out There aesthetically distinct with a simple visual style. "For the art, I have created everything with brush and ink on paper, then I colourised them with software.

"The result is something dark but fascinating, exactly the atmosphere we wanted for Out There.

I made sure to design very weird aliens to reinforce the feeling of encountering something you'll never understand as a human."

The visual design may have been a symptom of a tight budget, but the end result has helped give the game its own identity. "We were always very very very tight on budget and we had to do side jobs to pay the rent," admits Peiffert. "But it helped us in a way, because we felt like our hero, always lacking resources to go further."

Dark matters

One resource that won't run out in Out There, is 'stamina'. Being a premium game, Out There eschews the free-to-play payment model for a more traditional one. "There are many different reasons that led me to make a premium game," says Peiffer. "Launching a freemium asks a lot of money and that's something we didn't have.

But, even if we had the money, it's not the kind of games we are interested to make.

"Freemium games are designed around the goal of making money. Out There was designed to offer a full and unique experience. The game would not make much sense if we were selling fuel as in-app purchases instead of leaving the player drifting in the void forever. As a two-man studio, we don't need to make millions to be profitable. Out There was profitable three weeks after release.

"It's weird to think that freemium publishers have arrived to a point where they buy their players. I don't want to be part of this. We worked hard on this game, took insane risks and we are glad players loves it and pay for it."

It's good to see that the premium model can be the right path for a small developer to take. Handled right, it's a model that can benefit both players and the developer without having to step out into the coldness of space without a spacesuit.

Like Out There's default ship can be swapped for something more powerful, Mi-Clos also plans to upgrade the game's performance. A PC version of Out There is currently in development, which plans to add more content to the game. The extras will be added as a free update to the existing mobile version.

Peiffert had a dream of developing games and now it's Out There.