During our talk with company founder Alex Fleetwood, he described his firm as a 'game design agency', but it's worth noting that the company doesn't exclusively work in mobile, or even in video games.

Consider Drunk Dungeon, for instance. Commissioned by the NYU Game Center, this game of fantasy tactics used beer mats as game pieces and map tiles, and was designed as an 'ambient party game' that allowed players to get as involved as they wanted.

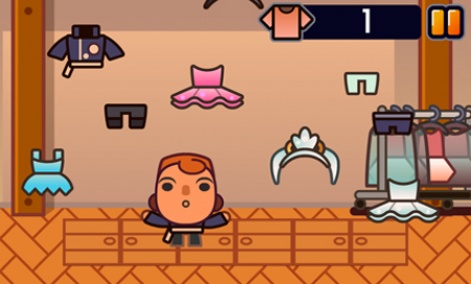

The Show Must Go On is another example of Hide&Seek's work, and represents its standout mobile release. Developed for the Royal Opera House, it's a collection of mini-games based on various aspects of successfully staging an operatic performance.

To find out about the company's backstory, its forays into mobile and his forthcoming keynote at the ExPlay Festival, we caught up with Hide&Seek director Alex Fleetwood.

Pocket Gamer: What kind of work does Hide&Seek do, and how did the studio start out?

Alex Fleetwood: I founded Hide&Seek in 2007, and before we were a studio, we were a festival of games in public spaces on the South Bank in London. So one of the core ideas of the studio is the notion of games in public spaces.

That's a trend that's been on the rise for the last 10 years with the rise of gaming on mobile devices.

Sitting alongside that is the idea of games a kind of cultural activity. You know, we go to a museum, we go to a theatre, we go to a gallery but where could one go to play games, and what kind of games would you play there?

We still put on events and festivals such as a regular event in London called the Sandpit, and we also run a festival called the Hide&Seek weekender and back in 2008, when we started putting these events on more regularly, we became aware that about a third of the people who attended the events did so to observe, and to scratch their chins and figure out what it all meant.

They came from brands and marketing and broadcasting and media companies, and sure enough, we started to get calls from people saying "we like what you're doing, can you come and do that for us in different ways?"

That's essentially led to a pretty successful game design agency Hide&Seek.

We work with a bunch of different clients to create things, and we consult on game-type things too. A lot of people come to us having heard about gamification now I think the concept behind gamification is a really good one, but the implementation is often really really poor so we try to steer people towards interesting things there.

We've made games for the likes of PlayStation, Warner Brothers, and we've just finished a Skyfall MI6 text adventure that was sponsored by Sony. It's a sponsored piece of content, but it's doing some fun things with the genre, too.

You said that gamification implementation is often very poor can you give us a mobile example of the kind of poor implementation you're talking about?

I think the problem is often that you have a client that wants to make a game or something game-like, and it goes to its agencies of choice its digital agency, its marketing agency and its media agency.

So they say to the marketing agency, "come up with an idea for a game."

Then they say to the digital agency, "build that game."

And they say to the media agency, "promote that game."

So you've got three different companies none of whom employ any game designers or game makers trying to collaborate to make a game. I think that has yielded many a disastrous project.

The Show Must Go On

Smart companies ought to be going to big name indie game designers and saying, "here is a lump of money make us something amazing." That is where things are heading, I think, and ad agencies are finally getting their heads around the idea that game designers are talent for them to work with.

If you want a brilliant TV ad, you go to a great director, and it's the same for games.

Last year, Hide&Seek developed The Show Must Go On, an iOS game for the Royal Opera House. Presumably that title had objectives other than pure profit, so how do you judge the success of a project like that?

I think the game was a critical success, but not a commercial one, for us.

It was highly regarded, but I think our aspiration with the project was to see whether we could take Royal Opera House content and see whether we could put it in a format that would appeal as a mainstream iOS gaming proposition.

Looking back on it, maybe we should have doubled down on the crazy operatic side of it, instead, and made something a bit more out-there. I am really pleased with the game.

But when you're working with partners from the art and culture sector, there are a lot of lessons to learn in terms of getting these things right.

Lots of people outside the games industry still think of games as a product things that you launch, you see whether they do well or not, and that's the end of that.

The thing we're increasingly trying to communicate to our clients is that, if you want to stay competitive, you need to deliver a service and commit to updates, refreshes and a relationship with the player. That's what the really successful studios are doing, after all.

When you're working on a project like The Show Must Go On, do you feel restricted by the need to design something for a client, rather than conceiving of projects and ideas yourself?

I think it opens up as many opportunities as it creates restrictions.

It's part of the ethos of our studio to be collaborative, and I want to see our work as part of a broader cultural continuum that includes different entertainment formats.

We also bridge the gap in terms of understanding with those organisations. I think that every time we collaborate with a company or cultural organisation, we leave them a lot more game-literate than when we started.

The Show Must Go On

We want to represent the right of games to be part of this cultural conversation, and it's something that's important to me personally and, I think, for the wider industry generally.

What will you be talking about during your ExPlay Festival keynote later this week?

I'll be drawing on a few different strands, all of which come under this concept of Games With Audiences, because I think that's a really important trends that can be traced across all games platforms to varying degrees.

In indie games, for example, we're seeing event games like J. S. Joust. It's intended for social play, it's a fun game to watch, and the boundary between game player and audience member is very very slim.

Then there's the arcade games, where a developer chooses to stick their game in an arcade cabinet and tour it around, rather than releasing it online, for instance. And the rise of esports as a spectator activity is also something that plays into this trend.

So, something I'll be looking at in the talk is, what the cultural trends that are driving this new space are, and what the design and production solutions for what future commercial games with audiences might look like.

On smartphones and mobile devices specifically, we're exploring prototypes for apps and games where the smartphone is the enabler of a social experience rather than the end point.

Thanks to Alex for his time.

To find out more about Hide&Seek, visit the company's website, or visit the ExPlay Festival on 2 November 2012 to hear Alex's keynote.