(Bear with me, here.)

Instead, my place has highly washable floors throughout something that, having previously lived in a house with more coffee stains on its carpets than I care to recall, was a necessity for me.

Of course, so washable are these floors, that that's what I spend a lot of my time doing. All the dirt that a naff carpet pattern might hide is there for all to see.

The spills, the slops, the random ginger hairs that appear to materialise out of nowhere I can see them all, and ultimately I can't resist getting out a cloth to wipe each mark away one by one.

Like Peter Molyneux's Curiosity what's inside the cube, my flat's floors are an OCD sufferer's dream.

Just-one-moreism

In my book, part of the appeal of Curiosity is that, like a quick bit of floor wiping, it's so simple a task that it actually seems daft not to join in now and again.

Such is the number of people already taking part, that even what is likely to be a mammoth task tapping away at all sides of a huge cube to wipe away just one of what could be a multitude of levels seems achieveable.

Throughout the course of my play today, I've zoomed in on various areas of the cube, mentally made a note of the section I want to clear, and set about it.

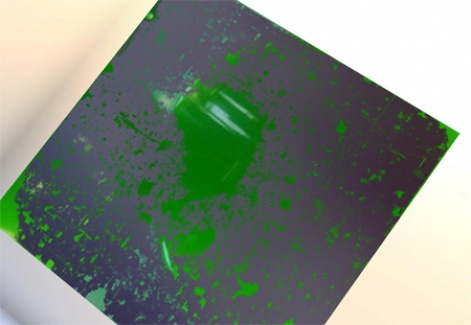

Before you know it, you've turned your screen entirely green, picked up the handy score bonus, and swiped to the left or right to have a crack at 'just one more' section.

Indeed, just-one-moreism (as I've just coined it) is what Curiosity relies on. It's exactly the same urge that grips me whenever I pass a random stray hair on my otherwise clean floor: it's not doing any harm, but when it take so little effort to clean it up, why wouldn't I?

So protective have I already become about the areas I choose to clear that I've physically jerked back on the few occasions when someone has got there before me. It's genuinely annoying when the game on your screen catches up with the global one, and suddenly wipes clean the area you were working on.

Curious dismissal

Are other players tackling the cube in the same way? I haven't a clue.

However, assuming Molyneux is keeping track of the game's analytics and I'm pretty sure he will be then, come the end of the experiment, he'll know exactly how we all played and when.

It's not unreasonable to assume that he'll be able to make a good guess at what the way we played says about each one of us, too.

And we mustn't forget, that's exactly why Curiosity exists. Here I am, less than a day in, questioning not only why I'm playing the way I am, but the way other people are playing, too.

I've already witnessed people making rather sarcastic, almost snobbish comments about the game in the few hours it has been live, yet there's one thing we can't deny: it has got everyone talking.

Molyneux's motivation

When we spoke to Molyneux at Unite 2012 in Amsterdam back in August, this is exactly what he wanted to achieve.

All of 22Cans' titles, save the last one, are investigations into how we play, what we like doing, what we don't, and how best to meet our needs as gamers.

Almost everyone who has dismissed the game today has, more than likely, downloaded it and had a go at it, too. But even if I was the only one in the world playing Curiosity right now, then that would in itself tell Molyneux something.

"The things I'm looking to learn are, firstly it's about motivation," said Molyneux at the time.

"Phones are with you all the time, so there's never an excuse not to play. If it's a failure or it's a success, we can still look at the bits that didn't work and refine what we're doing."

What's more, Molyneux is looking to publish everything he learns for hopefully the good of other developers. To be able to launch an experiment that gathers a large enough audience to make said results in any way meaningful is something not many mobile developers could muster.

Tap happy

Whatever you may think of Peter Molyneux and his career, I personally view this as quite a noble venture.

It doesn't really matter whether you think Curiosity as a game is a waste of time or not the fact is, Molyneux is one of a relatively select group of developers that has the pull to carry out a move like this.

Whatever the 'life changing' thing at the centre of the cube is doesn't really matter to me in reality, it's merely acting as the well publicised carrot on a stick that's likely to keep a certain bunch of players tapping away until the very end.

What Curiosity represents is an attempt to get to grips with the mobile market one that's evolving at such a rate that even the most successful of studios often has little idea why they've amassed the audiences they have.

Most developers have neither the time nor opportunity to take a step back and work out the rules of the game - they simply try to learn on the go. What's more, as the marketplaces themselves get larger, so the chances of pinning down a winning formula get more and more remote.

Molyneux's Curiosity is an attempt to put some numbers behind the theories, and to deliver the analytics that could and should result in developers knowing just that little bit more about the people they're trying to connect with.

As such, there's nothing curious at all about Curiosity. It could prove to be exactly what we need.