The first thing that you need to know about big data is that big numbers in the games industry especially with regards to active users, profiles, reach, and so on are almost always nonsense.

And if they are not nonsense, then they're probably misrepresentative.

The basics

Knowing that product X has however many million users doesn't tell you much about that audience, besides the obvious fact that they all downloaded the same game.

Still, that audience is a commodity, right? It has value, right? An audience can be sold as a collection of impressions to other game publishers, who can place ads for their own products.

For better or worse that is right, but just pushing out the same ad to every player is not a very effective method of leveraging an audience. The ads need to be tailored to have any chance of generating actual downloads - what the industry calls 'conversions'.

To do that, you need to learn more about your audience who that audience is and how it behaves is much more important than its overall size.

The process of categorisation required to do this effectively is called segmentation.

The process

So what do we want to know first? Well, first we need to know if our data system has seen a user before, or if it is seeing this user for the first time.

The first clutch of information we grab is some pretty dry technical stuff. Maybe a device identifier, a MAC address, an IP address (and hence the territory) and some other basics, depending on the platform.

Having scraped our audience of 50 million for this data, we may no longer be looking at one pot with all the users in it. Instead we have maybe ten pots, each containing a portion of the whole.

Let's say one of those pots, or segments, is called 'France' and it has five million players in it. Now we see why 'reach' as an audience metric for leverage is often misrepresentative, at least in terms of the perception of the value that a large reach offers.

After such segmentation, developer Y who has a deal with the owner of audience X isn't having their ad for Gaelic Folk Music Hero targeted at 50 million potential players, after all, because the French users in the France pot couldn't care less and will never download the product.

The developer is therefore only reaching a much smaller segment of 50 million.

And we haven't even begun with the real segmentation yet. All we know about the segment called 'France' so far is where they live, the device they are using, and their OS. That's all very useful, but we still don't know anything about them as gamers.

Kinds of gamers

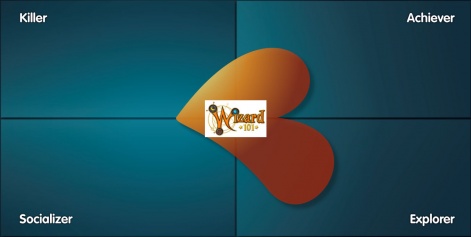

Here we can look to Richard Bartle's archetypes to help us.

Originally conceived as a way of categorising players in MUDs - the text-based precursor to what we now call MMOs - Bartle's famous paper on player archetypes ('Hearts, Clubs, Diamonds, Spades: Players Who suit MUDs' 1996) has proved one of the most enduring methodologies for categorising gamer behaviours, and hence gamers.

As you can see from the graphic above, there are four main archetypes: Killer, Socializer, Achiever, and Explorer.

The four archetypes are comprised of different kinds of player behaviour. For example, the Killer spends more time in competitive gaming, the Achiever more time hunting down rare loot, and so on.

These gamer segments, with the right tools, can be applied to an audience and cross-referenced against all that dry technical segmentation data to derive more data about a user's preferences and hence the types of games they are most likely to be interested in downloading and playing in the future.

Beyond Bartle's archetypes, it's possible to get much more granular with the segmentation process. This is where mobile and the notion of platform interdependence really comes into play.

How are segments useful?

In the fast-changing mobile games industry, especially where freemium titles are concerned, it is increasingly common to hear industry luminaries talking about the 'quality of users'.

What does quality mean in this context?

Well, big numbers of users are next to worthless if those users only ever visit the game once, and never pay for one penny's worth of content.

The types of users that savvy developers should be looking for instead are those that enjoy the game enough to keep playing it for a prolonged stretch, during which they pay for content and wax lyrical to their friends about how much fun it is to run their own theme park, safari, hotel, apartment block, space station, game design studio, or public toilet.

A granular segmentation of the audience for advertising and cross promotion purposes is the most sensible way for publishers to home in on these quality users that is, to find the right highly-engaged gamers who will enjoy and promote that particular publisher's titles.

And mobile offers unique segmentation opportunities, compared to other platforms.

Given the staggeringly high number of game releases on mobile, it's possible to refine and validate segments more effectively than on platforms that tend to have fewer monthly releases.

Mobile is also a fertile ground for observing the emergence of new player segments. Where exactly does Draw Something and its intimidating audience numbers fall into the established segmentation paradigm?

At iQU, we turn to something called the GamerGraph, which identifies at least 42 sub-segments of Bartle's four main archetypes across a range of platforms (see image above).

Imagine how small each segment of that 50 million audience now looks!

The future

Segmentation can reveal all kinds of player traits and preferences, and the interesting thing about these in the mobile realm is that they're not all specifically game-related.

Compared to other platforms, far more social and lifestyle data can be drawn from mobile, which can then inform player segmentation across other platforms. That in turn can help with predictive modelling for a range of interesting tools.

Segmentation may seem like another component of the crass commercialisation of the mobile games industry, but the net result can be exposing customers to the products that best suit them, better UIs, more culturally-bespoke content, and in some cases better games.

So what comes after segmentation? The name of that particular game is 'targeting', which I'll be dedicating more column inches to next week.

Part 2: Targeting

You can follow Fraser's industry commentary on his blog, or else grab bite-size rants via Twitter.