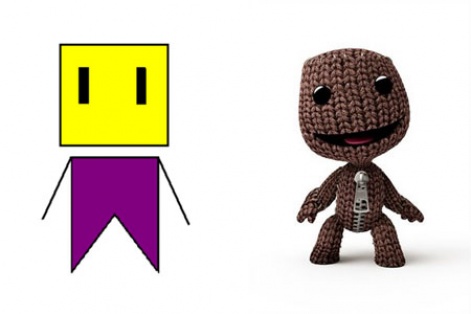

Have you ever seen Yellowhead? He's the blocky lead from the original concept game that the folks behind LittleBigPlanet first took to Sony to win its support back in 2006.

A video showing Yellowhead – a 2D, almost stickman-like fella who later became Sackboy – dancing around a similarly stripped back world was played by Dr. Maria Stukoff of PlayStation First during Manchester Tech Nights.

For a game with such an iconic look, it was something of an eye opener to see its more humble beginnings.

Dr. Stukoff's point? Too often developers pitching for publisher support try to come up with a finished article, when in reality, what the big boys and girls with the money want is an idea.

Great looks, shame about the game

Indeed, what many indies consider to be a finished article isn't actually the finished article at all.

While once working on an indie game brought with it a certain amount of freedom when it came to visuals – pixel counts or refresh rates left to the triple-A outfits – now there's a certain amount of pressure that comes with working on an indie game.

Like opening an independent coffee shop and making sure you have an appropriate number of hipsters on staff, people expect indie games to come with a visually distinctive approach – they may not push the boundaries when it comes to hardware, but in terms of reflecting design trends and digital fashion, they're now meant to lead the line.

The end result of that, of course, is that many indie studios taking games to publishers are far more fixated with how their game looks than how it plays.

Many indie studios taking games to publishers are far more fixated with how their game looks than how it plays.

As Dr. Stukoff accurately suggested, a publisher can help with the overall sheen of your title – they can even suggest a different art style if they think it'll make the game more commercially appealing – but they cannot polish a turd.

Games aren't art

Which is why, when you take a game to a publisher or a platform holder, it's the game concept – the bare bones of what people actually do in your game – that needs to be your focus.

Showing off a game that looks the part but is still sketchy when it comes to actual gameplay will do little but showcase the talents of your artist. If you can't explain, or demonstrate, what the goal of your game is in a few minutes there's very little chance the people you're pitching to will have any confidence whatsoever that you can deliver it.

As LittleBigPlanet proves, settling on a visual style is part of the journey, and something a publisher can actually help you with. Turning up with a game that looks fantastic but doesn't yet play well is the visual equivalent of pitching a fool proof monetisation method without a game in place to wrap it around.

A publisher won't make your game for you, but they will help you turn a promising concept into a commercial entity if they like your idea.

Don't get distracted by visuals. Don't lose focus. Don't spend your time searching out the next Sackboy when Yellowhead will do.