Yaniv Nizan is CEO of SOOMLA.

The mobile ecosystem is evolving fast. It seems like it was just yesterday when app stores launched and the gold rush of developing apps started. Back in these early days, apps didn’t contain advertising or in-app purchases, and no developer had analytical tools to optimise their apps.

Users paid for apps without question because they were a novelty. This has changed quite a bit in the last years, and we are now going through another such change in app monetisation.

This article is focused mainly on gaming apps, which have been the largest category in the app stores and amounts for roughly 50% of the revenues.

For the past four years, app developers have been competing against millions of apps. To make them more enticing, developers have made them free-to-play, a revenue model supported largely by in-app purchases and, to a smaller degree, ads.

But developers whose games are beyond the top 10 highest ranking in the app store are more likely to employ in-app ads. And, within the gaming genre, card and dice games and simulation ones have the most in-app ads followed by casino games.

Overall, more than half of top grossing 100 gaming apps monetise primarily from ads.

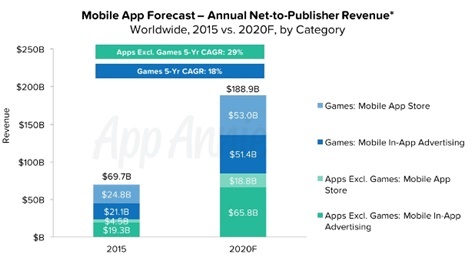

According to App Annie, increased monetisation from ads will generate $50 billion in revenue for gaming apps by 2020 and up to $115 billion for apps overall.

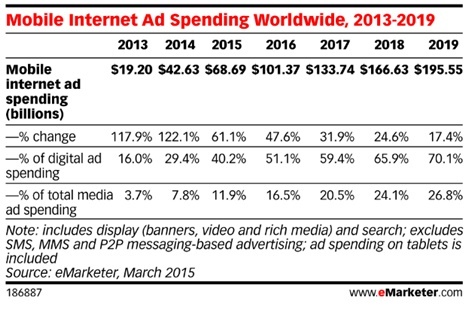

Mobile ad spend is predicted to grow in tandem with an estimated $195 billion, according to eMarketer.

These two forecasts mean that there is a fairly big shift in monetisation models coming to mobile apps in general and mobile games especially.

A brief history of gaming apps

When the two major app stores first opened, most apps used the pay-to-play revenue model. The apps were a novelty, and people paid to download.

That model gave way to the free-to-play (or freemium) games that are now the constant for generating revenue from in-app purchases, such as upgrading to a premium version of the game or purchasing accessories to enhance play.

In-app ads are also part of that revenue, but their use is increasing as another way to monetise. Thus, the revenue model is shifting. App Annie predicts that in-app ad spend will be circa $101 billion this year and cites that games will take home a significant portion, much from the display of video ads.

The emergence of view-to-play

While in-app ad revenue is new to the top grossing games, one can’t ignore the growing revenue within the Facebook app. Gaming companies could not have stayed indifferent to the news that Facebook made more than $17 billion in advertising revenues during 2015 and is expecting to reach $25 billion in 2016.

While in-app ad revenue is new to the top grossing games, one can’t ignore the growing revenue within Facebook.

In early January, it announced exploring the use of mid-roll ads as commercials that interrupt a user’s viewing of a video (even if the video is only a few minutes long). Ads are a minimum of 15 seconds in length, and users must watch them to continue the video.

Critics fear of repelling audiences who are likely accustomed to ad blockers and other ways to avoid ads. Others believe there is a general tolerance for ads and sponsored content in which this method of ad presentation will pose no impact.

With gaming apps, in-app ads is growing strong. Again, App Annie predicts that in-app ad revenue will increase among many games as a way to further monetise from free-to-play users.

One driver for this change is that the addition of in-app ads allows companies to increase the lifetime value of a user (LTV) also known as the average revenue per user (ARPU). Increasing the LTV has become more important than ever for app companies due to the increase in the cost of marketing.

In 2016, the average cost of generating an app install through marketing (CPI—cost per install) has grown significantly. This new reality puts a lot of pressure on app makers to decide between two options: either decrease marketing which means less growth or generate new revenue streams. Many are choosing ads as a way to generate new revenue streams from users not making in-app purchases.

SuperData Research also suggests that the change is in part because users are changing and not spending as much on in-app purchases that have largely driven game revenue to date.

Finally, having an incentive, such as gaining an additional life in the game or moving forward a level, aims to keep users engaged and prevent churn while ads are displayed.

Opt-in ads are considered a less intrusive way of designing ads into games and has allowed game companies to warm app to ads and introduce them in more subtle ways. In many cases, the opt-in ads are the first step of a game company into the world of in-app advertising.

There are concerns of users leaking to other apps, however, we conducted a study at SOOMLA, of which I spoke about in a recent podcast with Cranberry Radio, where we observed that players who are already engaged with the game are highly unlikely to leave it because of in-app ads.

That’s a positive sign for this developing revenue model.

Free-to-play sparked games-as-a-service and analytical tools emerged

Following the adoption of the free-to-play business models, game companies have adopted a new approach to managing their businesses: games-as-a-service. This follows the best practices from the realms of software-as-a-service products and other service-oriented businesses.

These best practices included to a great extent a great dependency on data analysis tools in different areas of marketing and product.

First, the marketing strategy of these companies became mostly about measurable performance and returns on every dollar spent. In other words, how much you spend and make on each marketing activity.

These companies made significant investments in third-party analytical tools, allowing them to measure which users came from each campaign and at the same time tie revenue from in-app purchases to the same users so cost and returns could be compared for each activity.

This practice is mostly referred to as ROAS - return on ad spend. It’s also common for these companies to think about ROAS in unit economics - calculating it for a single user where ARPU (average revenue per user) is bigger than the CPI (cost per install).

A key practice in games-as-a-service is the ability to segment and personalise the experience between different players.

A second tool that has evolved in the years of free-to-play is A/B testing and optimisation. The ability to compare the revenue generated by different product variation unlocks a highly effective practice of evolving through iterations.

If you can constantly try new things and select the one that is slightly better than the other, you can make a series of 1% improvements resulting in a big compounding impact on your revenue. Here again, another significant investment in analytical tools was made to enable the testing infrastructure.

Finally, a key practice in games-as-a-service is the ability to segment and personalise the experience between different players. Companies have evolved highly sophisticated CRM tools where they store a comprehensive profile for every user based on his demographics and in-game behaviour.

A key part of the profile is the purchasing history of the users. This allows the companies to find their highest value users and learn more about them.

View-to-play disrupts analytical tools

Early adopters of the view-to-play model have realised quickly that the ability to follow the games-as-a-service practices is now facing a threat.

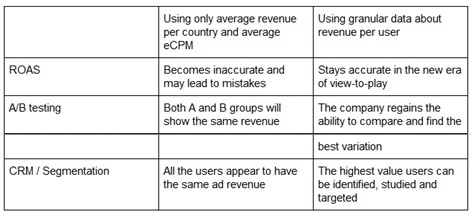

The tools they have built are not accounting for the new revenue made from in-app advertising. ROAS calculations only account for in-app purchases; A/B testing misses the revenue made from ads and the CRM has no details about the user interaction with the ads or the revenue made from them. Suddenly the practices of games-as-a-service have stopped working.

All these problems are really a result of one single fundamental problem: The companies don’t have access to data about ad revenue per user (as opposed to averages per country).

One might think that feeding the averages to the existing tools is a good solution, but it may result in making these highly expensive tools dysfunctional. As we all know, the famous rule of data in computers: “Garbage in, garbage out.”

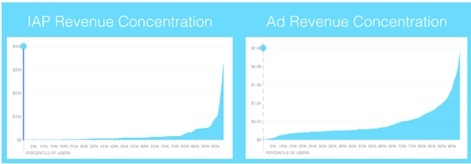

Part of the importance of these tools stems from the big variance that exists in the revenue that two different users can generate from ads.

As presented in a research made by SOOMLA, a single user can generate $74 in a month from in-app advertising and in general the 80/20 rule applies to in-app advertising revenue almost as much as it applies to IAP.

As more ads are displayed, the need for objective, third-party measurement grows. Marketers need to effectively calculate their ad revenue per user and visualise it on its own per eCPM and as part of the bigger picture of profit in addition to user fees and in-app purchases.

Critical need for third-party measurement & ad LTV

A knee-jerk reaction to the prospect of using third-party measurement tools is, “Why bother? We can build what we need in-house”. The reality is, however, that tracing ad revenue per user is highly complicated.

Other ad networks didn’t want to share the data. They just don’t want to share with other firms. There is no cooperation there.Guy Tomer

The ad networks are not cooperative about releasing this type of data, and solving the problem with data science tools requires a significant investment in researching every ad network to understand its business models and the way its SDK operates.

Furthermore, the algorithms used to drill into the aggregated earnings and extract the granular ad revenue details from multiple ad networks are complex. Such a system needs to track ad interactions, post-impression performance and SDK and API updates for hundreds of networks.

One company that tried to solve this problem in-house is TabTale. In a recent panel at Casual Connect, the CMO, Guy Tomer, commented: “Other ad networks didn’t want to share the data. They just don’t want to share with other companies. There is no cooperation there.”

As they were trying to get the data into their own BI system, they realised that even a publisher with one billion downloads doesn’t have enough leverage to get the ad revenue data from ad networks.

On the other hand, third-party solutions for the monetisation measurement problem are a reality. The advantages of using a vendor here are obvious:

- Faster path to value without waiting for a big internal R&D project to be completed

- Less risk and effort knowing that your partner is keeping the system up-to-date

- More robust feature set and integration with the rest of your data platforms

There are several third-party vendors in adtech who have emerged with varying capabilities to measure ad LTV. When considering contracting with a new vendor or to vet your existing measurement partner, consider the following questions:

- Would you be able to measure eCPM per device id?

- How would you identify the whales and create lookalike audiences of them?

- Would you be able to export raw data?

- Would you be able to get postbacks and API-level access for ad-revenue events?

Apps, which were a novelty a decade ago, are a mainstay for today’s games. For their sustainability, in-app ad revenue is the new frontier of app monetisation.

Apps that want to stay ahead need to adapt quickly to the new reality, and third-party measurement tools like SOOMLA and Kochava are vital to their success.