What would you do if you found a stranger's lost phone, unlocked and free for you to thumb through?

That's the question posed by A Normal Lost Phone, a game by French indie studio Accidental Queens that launched in January.

The best mobile game developers consider deeply the relationship between the touchscreen interface and their mechanics, but Accidental Queens goes one step further by using its own Android-esque frontend as a setting for gentle puzzling and an unfolding narrative.

But how did the concept come about, and what were the benefits and challenges of developing a game set inside a mobile phone?

To find out, PocketGamer.biz reached out to Accidental Queens' Programmer and Co-founder Diane Landais.

PocketGamer.biz: A Normal Lost Phone began life as a game jam project. Tell us a little about that, and the initial inspiration to set a game within a smartphone interface.

Diane Landais: During the production of the original prototype, back in January 2016, two main aspects drove the game design process.

We wanted to explore new ways of delivering a narration through an innovative interface, something that would be as immersive as possible and breaking the codes of the “choose your own adventure” genre that some of us had already explored before in previous projects.

The second aspect was the theme: we wanted to deliver a message on a specific subject, working especially on the empathy that could be expressed by the player in this kind of game.

We took inspiration from multiple directions: Analogue: A Hate Story and Her Story were both very important to us because of the way they handle non-linear mechanics in their narrative design.

Our love for the game Life is Strange probably shows as well, in the type of characters we chose to depict, as well as in the soundtrack.

With the original team consisting of four people, with different tastes and references, we didn’t have many influences in common; but every one of us had a different opinion on the proposed draft of the concept and added their own inspirations to the mix.

When did you decide that this was something worth expanding into a full game?

After the game jam, the prototype was in a playable state.

After the game jam, the prototype was in a playable state. It had a beginning and an end.Diane Landais

It had a beginning, an end, could be played in 30 to 45 minutes, was available in three languages (thanks to a team that spoke multiple languages, and the help of many friends helping on the translation) and carried an interesting core gameplay mechanic.

This is pretty rare for game jam productions, and we felt confident showing what we had made to some friends or communities that were close to us. Since it was free and playable in a browser, it spread pretty fast.

The online game hosting website Gamejolt held a contest to exhibit chosen games at GDC. We polished the game a bit more in our free time and submitted it there, granting us even more visibility (even though we weren’t selected for the contest).

After that point, word of mouth took over and the game got some attention from the online press. Many things could have happened then:

- Releasing the game as it was, for free;

- Keeping it as a hobby project, available online;

- Or working out what could or couldn’t work for a commercial project, putting some time and effort into it, and releasing it on mobile app stores.

All of us in the team had different situations - some were students, others had a day job - but we decided we wanted to see how far the game could go, considering it a good addition to our portfolios in any case.

Some of us then quit our day jobs to work on the game full-time, while the others kept it as a free-time project.

There's an inherently invasive aspect that comes with this concept of digging through a stranger's life, as revealed through messages and online profiles. It's divided opinion, but was it your intention for the player to feel discomfort?

Yes, this game is supposed to make people uncomfortable, because it is morally wrong to peer into a stranger’s intimate life.

The kind of secrets you uncover as you play make the player all the more aware that what they are doing is not okay.

Something happening at the end of the game was designed to make the player reflect about what they just did, and give them a chance to “make it right” by erasing the phone’s data.

But the option to erase the phone’s data is present even from the beginning. It is a valid ending - albeit one that doesn’t lead to many answers - and we wanted to keep it intact and accessible from the beginning.

While it might seem weird for a game to tell the player that “it’s okay to not play at all”, we think it still sends a message that this possibility exists.

However we understand how this concept can divide opinion. Using a phone is a common interaction, and the gap between fiction and reality is far thinner in this game than when you play, for example, a FPS where you have to kill everyone: you may despise violence in real life but still kill those NPCs because it is a fiction.

Some people are deeply uncomfortable searching through the game’s phone precisely because this seems so close to a real-life interaction.

We consciously removed a layer of abstraction, by having the player play as themselves and not a character.Diane Landais

We consciously removed a “layer of abstraction”, by having the player play as themselves, and not through an avatar or character to embody: in A Normal Lost Phone, the player has found a phone, and acts upon that with their own habits, prejudice and sensibility.

But all of this was done with a specific goal in mind: creating empathy, showing Sam’s story through a new perspective. The player isn’t a spectator, nor an actor; they see the story unfold as a witness.

All of this creates a closed space for questioning, interrogating, reflecting upon one’s beliefs and opinions. It’s about understanding how even a simple, seemingly trivial and uninteresting text message can have a deep impact on the character’s life.

It is as invasive as the players lets it be, but we have little doubt that after having played the game, the player will not feel that they’ve been taught that “digging through people’s personal life is the cool thing to do”.

Once the safe, constructed space of a fake phone that is explorable as part of a fictional piece fades away, after the credits roll, the feeling of discomfort fades as well.

The seemingly boring or uninteresting parts of our everyday life, however, won’t look the same.

There is something to take away from the game, but it’s not about its interface or mechanics - those felt wrong from the beginning. It’s about the experience.

Because the bonds that are created, the chance to understand, the space for introspection - those, hopefully, felt right.

How did you go about designing puzzles within the confines of the smartphone interface? At what level did you want to pitch the game's difficulty?

The first step was to list every smartphone app we could design, code and use as a puzzle environment.

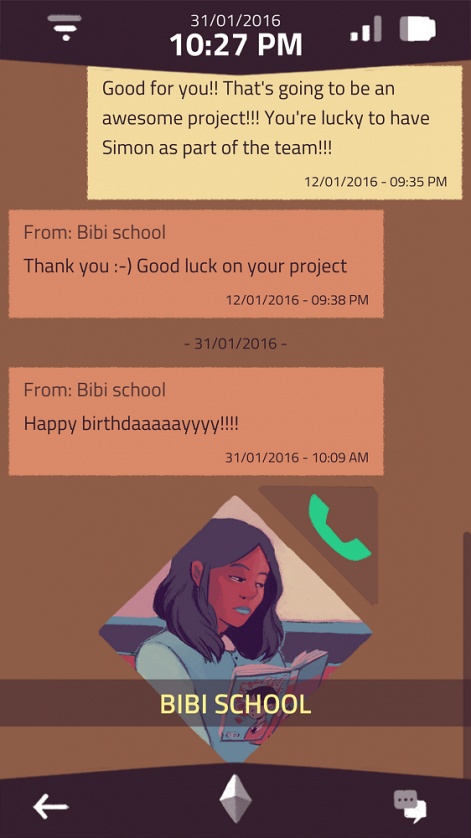

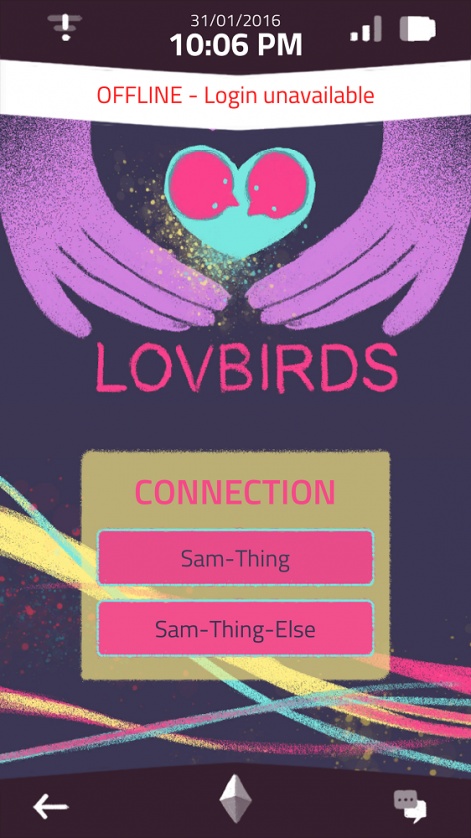

Some of them were obvious to have (like the messages), some were kept because they were interesting for the scenario (the dating app).

Some were cut from the prototype, like the music player, because it wasn’t critical and was out of the scope for the 48-hour prototype.

It eventually came back in the full version, along with a fully original soundtrack that ties nicely with the scenario of the game and helps build some background for the character.

Along with the apps, we also identified mechanics that made sense in a smartphone environment - once again avoiding anything that would be too hard to make, or did not align with our narrative goals.

Calling people and hearing them answer their phone, for example, created constraints we couldn’t afford to deal with, so we scrapped it and found a way to justify its absence from the game.

Taking inspiration from our own phones and habits, we quickly decided on using passwords to gate the content, as there are many places in a smartphone that make more sense with a password than without.

There’s no delivering the message if the player gives up halfway through.Diane Landais

But some of the puzzles are more complex, and more situational. I’ll try not to spoil any part of the game, but let’s just say that we tried to “hide things in plain sight” as much as we could.

There’s joy in finding the right password and seeing an app open up after a good guess, but a puzzle that has to “click” in the player’s mind; something that doesn’t tie to numbers or specific answers, but instead to some sort of comprehension, is really rewarding to see as a player.

We conducted many playtests, at various stages of the production. Depending on the player’s reading speed, ease of comprehension, and general puzzle-solving abilities, the game could be perceived as too hard or too easy, too long or too short.

We reworked anything that felt too hard, since we didn’t want to bring too much of a challenge: our goal is to deliver a message through the game, and there’s no delivering the message if the player gives up halfway through.

As the player digs deeper into the phone, there are some major revelations about its owner and their identity. To what extent is this a commentary on the role smartphones and social media have to play in the construction of ourselves?

Not much of it was thought as a deliberate comment. We did not try to bring an opinion on this subject through the game, though we did take inspiration from the kind of interaction and situations that it can create.

The fact that Sam, the owner of the phone, writes differently when talking to friends, family or online contacts is both pretty realistic, and an interesting fact to use as a gameplay element.

We’re more interested in seeing if, and how, the player will construct their mental image of Sam by seeing all these different pieces come together.

We only know that much about the smartphone's role in people's lives: as a communication device with different rules than real-life, face to face interactions, it depicts a different image of whoever is communicating because there is no tone to hear, no facial expression to interpret.

Is it something inherently good or bad, dangerous or exciting? For now, we don’t know, and that’s a complicated subject.

It is different though, and it varies between the multiple types of communications and the people we communicate with.

With the increasing gamification of social platforms (particularly Tinder, Snapchat, etc.) do you feel there's more scope for developers to create games based around everyday smartphone interactions? Would you welcome it?

There are two distinct trends related to the gamification of social networks/smartphone features.

Platforms like Tinder or Snapchat use playful mechanics and game design elements to serve their main usage. They are still social platforms above everything else.

Games that use social networks or phone apps as a setting for their gameplay and narrative are a different thing.

Platforms like Tinder or Snapchat use playful mechanics and game design elements to serve their main usage.Diane Landais

The biggest difference is in the content: games that look like apps are still games, with “fake”, fictional content. Apps that behave like games are apps first, with a purpose, for actual users.

It’s interesting to see where these two can meet, and we’re starting to see some great ideas emerge - Reigns for example, imitates the swiping mechanic of Tinder but uses it in a fictional world, creating something new and unique.

But the scope of using regular, “non-gamified” apps as a medium for storytelling hasn’t been fully tapped yet.

My opinion is that there’s probably more to do with apps that everyone already knows and uses every day, as game mechanics; rather than with new, innovative, quirky gamified apps that can already abstract part of the interactions between people.

It’s that seemingly simple bond between people that helped us build our narrative for A Normal Lost Phone, and I think we needed the simplicity of a bare messaging app more than a playful take on a picture-sharing social network, for example.

All in all, do we feel there’s more scope? Unsure. Would we welcome it? Definitely.

How big was the team on A Normal Lost Phone and how long was the total development time?

It started as a four people team - Elizabeth Maler, Diane Landais, Estelle Charrié and Rafael Martínez Jausoro - developing a prototype in 48 hours during the January 2016 Global Game Jam.

Three people were then added to the team to continue working on a commercial version, and it was made in roughly a year.

At first, everybody was working remotely during their free time, and it wasn’t until September that part of the team started to work full-time on A Normal Lost Phone.

The release date was on the 26th of January 2017, about one year after the game jam prototype was made.

How do you reflect on the game's launch? Are you happy with the reception thus far?

We are very happy. We had a lot of very nice reviews, both in the media and from players. The sales are also quite good for a very small indie game, whose initial budget was low.

Are you able to share any early sales figures?

We can’t share any exact number, but we’ve recently passed 20,000 copies sold.

This number is hard to compare with other games, since every game behaves differently as a commercial product.

We had a free prototype of the game playable online for a good part of the year prior to the release, which means many more players have played A Normal Lost Phone (albeit a very different version) than just those who bought it.

The price of the game is similar on Steam and mobile stores, which results in a “cheap” game on Steam, driving more players to discover it for this reason.

What have you learned/are you still learning from A Normal Lost Phone, and how has it impacted what you're working on now?

We have learned a lot, both during the production and after the launch of A Normal Lost Phone.

We have identified how we could iterate on this first game and improve the next one, from a game and narrative design point of view.

But we have also learned a lot about teamwork, like how to make the most of everyone’s skills or how to make sure no one feels left out.

We are still learning from reviews, discussions with players and other developers, and this will definitely have a huge positive impact on our next productions.

You can buy A Normal Lost Phone on Google Play and the App Store.