Image: italianestro / Shutterstock.com

This article was originally published on August 29th 2016. In light of the news that GREE has closed its Western studios and operations, less than a year after DeNA shut down its US subsidiary DeNA Global and ngmoco LLC, we have republished this article to provide an in-depth insight into the problems faced by these companies.

Five years ago, I was walking over the Hohenzollern Bridge in Cologne on my way to Gamescom when I received a phone call.

It was someone from Japanese mobile games platform GREE.

They were complaining about a story I had written about the company's recent quarterly financials.

Apparently, I had used an incorrect currency conversion between yen and dollars.

GREE announces its numbers in yen and I'd converted to dollars at the rate of the announcement day, not the rate at the end of the quarter.

My dollar revenue figure was, thus, too large.

'If you don't correct it, the percentage increase in sales you write next quarter won't be correct. It won't be big enough," I was told.

True story.

But that was then

The reason I recall this incident so strongly is nothing better demonstrates the crazy growth of the early 2010s.

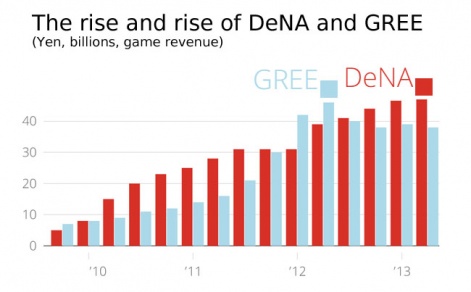

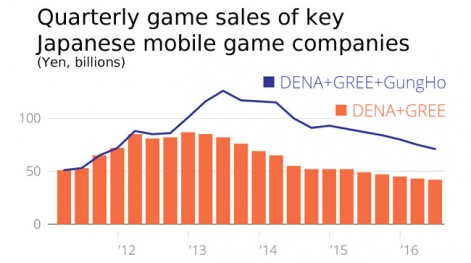

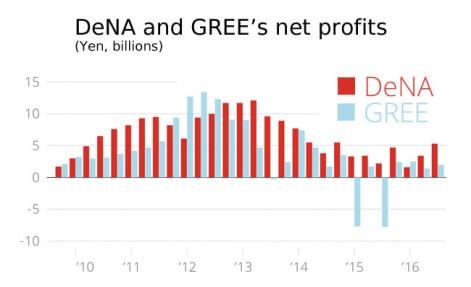

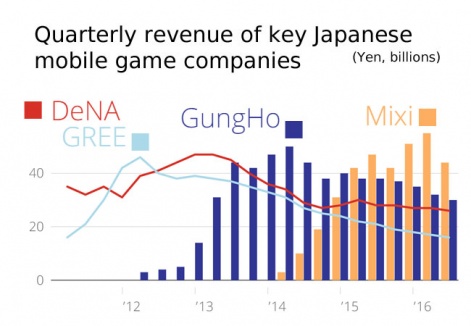

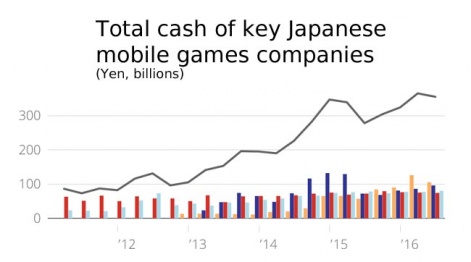

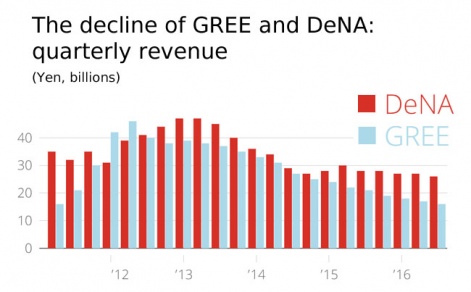

The whole mobile games industry was growing double or triple digits, and with +30% margins Japanese platforms such as GREE and arch-rival DeNA (pronounced D-N-A) were some of the most profitable games companies in the world.

Apparently, they didn't care whether you got their revenue numbers correct, or not.

GREE and DeNA were prepared to spend big to get more growth.

But they certainly cared you got their growth numbers right.

And they were prepared to spend big to get more growth.

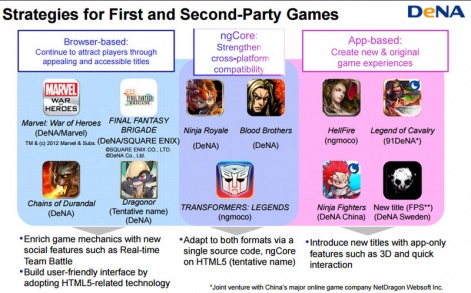

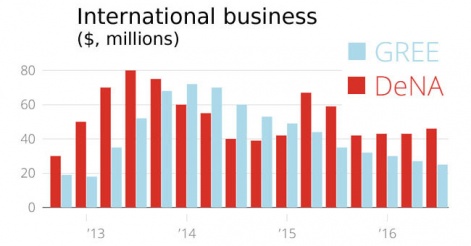

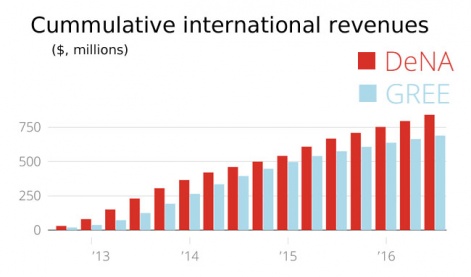

Between 2010 and 2012, DeNA announced a $400 million deal for US startup Ngmoco, GREE followed up with $100 million, $200 million and $170 million deals for OpenFeint (US), Funzio (US) and Pokelabo (Japan), respectively.

(In keeping with the times, Nexon bought Japanese mobile game developer Gloops for $490 million in cash, but that's another cautionary tale.)

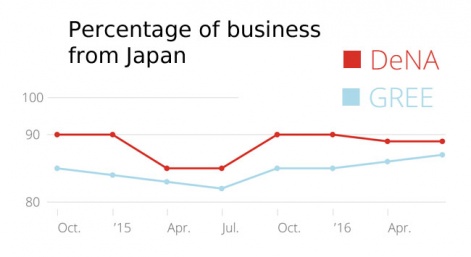

Fast forward half a decade and the mobile games industry has matured to single digit growth, and GREE and DeNA have long retreated from their plans of global domination.

The only numbers they care about are profits.

The quarter-on-quarter revenue percentages are all negative.

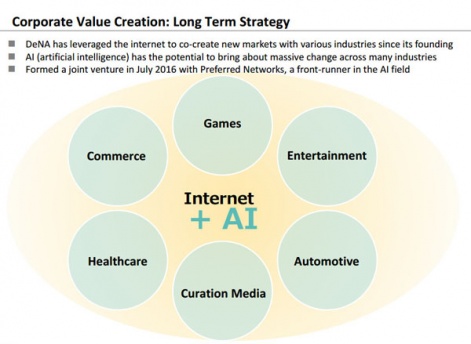

Licking their wounds in Tokyo, they are looking outside of games but within Japan for future growth.

DeNA now breaks down its financials into 'Sports' and 'Excluding Sports' categories.

Both have plans in healthcare and general online commerce, while DeNA is also doubling down on its baseball franchise, the perennially sixth-placed Yokohama DeNA BayStars.

Indeed, despite games being 68% of total revenues, it now breaks down its financials into Sports and Excluding Sports categories.

Heart of the matter

So what's this cautionary tale really about?

Fast-growing companies over-expanding, spending their cashflow imprudently, hiring badly and losing focus?

Yes, but the cautionary tale of GREE and DeNA is more.

It's about what happens when companies believe they are special; that they have cracked the market, when in actuality, they are riding the wave, not understanding how little they understand, and how quickly the market is changing.

At its heart, then, this is a cautionary tale about not understanding the fundamentals: about not understanding mobile games.

Click here to view the list »