I recently published a mini-book about one of the most-hated game mechanics in free-to-play.

Delay: Paying Attention to Energy Mechanics is a leisurely afternoon read, and my hope is that it takes a nuanced approach to a controversial subject.

It brings together theories from queer studies and anthropology with developer interviews and reviews of five important games that use energy mechanics, to explore why energy mechanics are hated by some and tolerated by others.

Barrier to more fun

'Energy mechanic' could mean a lot of things.

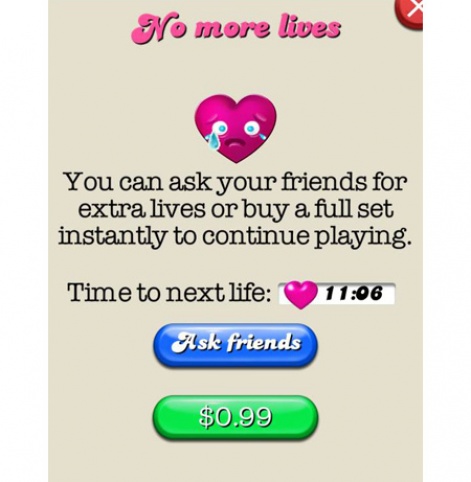

Here I'm specifically discussing the conceit in casual and mobile games whereby every action drains a resource of some sort - normally it's 'energy', but it could be' fuel', or Candy Crush Saga's 'lives' system.

Energy replenishes gradually over time, like your own energy does when you take a rest, but when their energy runs out players are solicited to buy more in order to keep on playing immediately. Most players just turn off the game and come back to it later on when they have enough energy to continue.

For the majority of players, casual and mobile is a waiting game.Zoya Street

There are lots of reasons to feel annoyed about energy mechanics.

Many argue that it's manipulative to create an addictive game, give people a taste for free, and then charge people to keep on playing right at the moment that they're completely engrossed. This is what is meant by the 'drug dealer' analogy.

More fundamentally, it's deeply frustrating to be told you can't play a game anymore. And why would you want to turn players away? Don't you want people to keep playing?

Delayed gratification

All of that is valid, but it doesn't quite explain why more players aren't turned off completely by the presence of an energy mechanic. Top-grossing, hit titles have employed the mechanic.

While it does stop people from playing for long individual sessions, millions of players are happy to come back to these games every day, to play for a little while, only to be told to pay up or leave. Most don't pay anything.

70 percent of the people who reached the final level of Candy Crush haven't paid a penny. That means, for the majority of players, casual and mobile is a waiting game.

In Delay, I explore what I see as a cultural difference between 'gamers' and the broader population of players. I explore why 'snacking' on a game might feel satisfying, why most people are afraid to get into a game for too long, and why gamers feel so offended by games that cannot be played for long sessions.

I also look into how children fit into this, not only as consumers of games but as cultural ideas that influence the way that we think about play.

Don't wait. Pay

To be a gamer or a game developer is to reject part of what society says it means to be a grown-up. Gaming is a subculture because it entails an alternative lifestyle, where play isn't completely opposed to productivity and there isn't such a strong divide between the things that nourish you and the things that are bad for you.

I don't want to overstate this point - game developers have to do tedious grown-up things just like everybody else - but the boundary between work and play is weaker.

We live in a world where some people have to wait for things that other people can just pay for.Zoya Street

Energy mechanics don't make sense within this culture, but in the mainstream world, where play is a distraction and work is paramount, they fit in just fine.

We live in a world where some people have to wait for things that other people can just pay for. If you find energy mechanics distasteful, I think this should be the reason why.

Holistic thinking

I don't think it's a coincidence that the social and mobile industry that is the home to most games that incorporate energy is so closely connected with Silicon Valley start-ups and venture capital.

Where else is it so easy to spend money to 'accelerate' a process that takes other people time and effort to achieve?

Look outside of games, and the darlings of the apps industry such as Uber are all about efficiently breaking up casual labour into snack-sized chunks. It's not just imaginary energy that can be bought with a microtransaction.

In the end, I think I come down neutral on energy mechanics. I don't think they're as annoying as people say they are, and I don't really see a problem with having my access to a game limited to small play sessions.

I think it is important that we start thinking about a more sophisticated critique of casual and mobile games - one that doesn't assume that work and play are completely separate, and instead sees how they are connected and what that means for cultural change in our society as a whole.

Delay: Paying Attention to Energy Mechanics is available for £2 at rupazero.com