John Romero, the game developer and designer of influential games including Doom and Quake, is about to publish his autobiography.

And thanks to Abrams Press, we’ve got a short extract here for you to read from chapter 23, subtitled “Open-World Exploration”. It’s the section of the book where Romero reveals how he turned to mobile games after leaving Ion Storm.

Romero was one of the first mega-stars of gaming. His work defined the first-person shooter genre. But he was also there at the birth of handheld gaming. The team at Monkeystone, which he founded after Ion Storm, was responsible for a number of titles, including the fun Congo Cube and the technically impressive N-Gage version of Red Faction.

After reading the book, we sat down with Romero last week to get additional commentary on his career, passions and skills. You can read that exclusive feature and interview here on PocketGamer.biz.

Doom Guy: Life in First Person by John Romero (Abrams Press, £21.99) hits shelves on Thursday, 20th July.

DOOM GUY

CHAPTER 23

Open-World Exploration

I was ready to explore.

For the past thirteen years, I had been making first-person shooters, from Hovertank One through to Daikatana, and I felt I had explored the highs and lows of shooter design. Likewise, I had experienced the best and the worst of company dynamics. My “eureka moment” at Softdisk with Dangerous Dave in “Copyright Infringement” led to the formation of id Software, while Ion Storm had been a roller coaster of challenges.

I thought about all of this in that last month as Ion Storm wound to a close as well as what opportunities were on the horizon. As we walked out of Ion Storm, Tom and I knew we wanted to continue working together, and there were numerous options to consider. The game industry had gone through so many changes, just in the last few years. Japanese role-playing games (JRPGs) dominated the awards with Chrono Cross, Final Fantasy IX, Dragon Quest VI, and The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask each taking a Game of the Year award from various outlets in 2000. The Sims, designer Will Wright’s game about simulated humans, created a new and interesting genre. Deus Ex managed to take home a BAFTA Interactive Award for Game of the Year, giving us a reason to celebrate.

Playing games on the go was going to be a massive segment of the industry soon, and I wanted to get in on the ground floor of the new mobile revolutionJohn Romero

In considering our next steps, we didn’t want to start another big company.

“I just want to code,” I said. The best times I ever had in game dev involved me coding for hours and hours and hours. “In my dream scenario, that’s all I’m doing. You design whatever it is,” I said to Tom, “And I’ll code it.”

I also wanted a break from the calamity of management.

At the time, the PC world was just getting off MS-DOS and onto Windows, and then a new kind of gaming platform emerged: the mobile phone. Early mobile phones were far from the smartphones that we have today, which are powerful computers in their own right with screen resolutions and processors capable of delivering exceptional play experiences. In the early 2000s, mobile phones had much smaller screens and most were two color, black on a green, gray, or blue screen. As primitive as they were, I knew that playing games on the go was going to be a massive segment of the industry soon, and I wanted to get in on the ground floor of the new mobile revolution that I was sure was about to take place. A handheld/mobile company was perfect for a small team, and it also put us in what we believed was an emerging market.

JAMDAT, a new company founded by Activision veterans in early 2001, was leading the mobile gaming charge. The hardware was beginning to improve, with faster processors and bigger screens, and soon the handheld PC market emerged. The most popular handheld PC was Compaq’s iPAQ. Compared to the limited mobile devices of the time, the iPAQ had a great-looking color screen, exceptional audio, a fast processor, and even early on had some decent games. That was the handheld we targeted for our first game. I was excited to code again full-time and learn C++, the Win32 API, and the iPAQ hardware (learning C++ was relatively easy since I was fluent in C, a language I adhered to because it was more performant, and working on shooters required every ounce of performance).

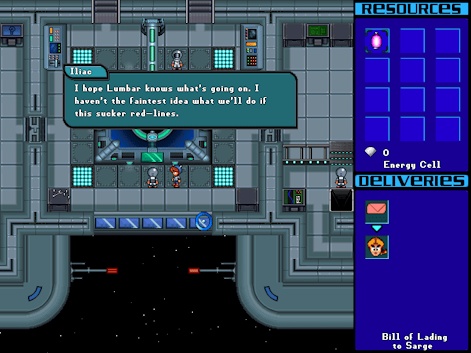

On August 1, 2001, the day after things with Ion Storm wrapped up, Tom and I founded Monkeystone Games along with Stevie Case, a level designer from Ion Storm. Tom handled design, I handled code, and Stevie handled business. As our first project, Tom designed Hyperspace Delivery Boy!, a top-down Zelda-style puzzle adventure game where the player takes on the role of Guy Carrington, a courier in training. Guy embarks on several dangerous missions in four different locations—all full of Tom’s signature brand of funny characters for players to interact with while solving puzzles and attempting to deliver various items. Hyperspace Delivery Boy! also had an action mode so the player could attack enemies as they solved puzzles and Panic Zones that gave the players thirty seconds to escape or die trying.

I was looking forward to writing the tools for Tom to make game levels, writing our game engine in C++ and the gameplay code in Lua. My last real programming stint was in 1995, using a NeXTSTEP computer and working in Objective-C. I also had to write all of the tools to collect and bundle game data, write a new level editor, build the game, and do a deep dive into Pocket PC hardware so I could put the game on it. It took me three weeks to write our tools in Windows, and another three weeks for the game engine—which was designed to function on both Pocket PC and other platforms, so we could sell it in multiple markets. We finished the game in four months, on December 23, 2001. Next up would be ports for Game Boy Advance, PC, Mac, and Linux. Hyperspace Delivery Boy! was critically successful and attracted a good following, but it wasn’t a breakout hit.

We moved from Hyperspace Delivery Boy! to Congo Cube, a match-3 game designed to be more action-based and wild than the current market leader, Bejeweled. Congo Cube hit high on my personal fun meter and joined hundreds of other games on RealArcade, a PC game store that released about a dozen games a week. Discovery, the process by which people find games, then, as now, was a challenge for game creators. Market leaders like PopCap Games had captured an audience with hits like Bejeweled and were able to advertise to that audience to promote new games. Others needed to spend significant money to advertise in those existing channels to attract players. It was an expensive proposition for most of us developing at that time. Mind you, this was years before the iPhone and the App Store combined to create the biggest casual gaming market on the planet.

Our next project was to develop a port of Red Faction, a PlayStation 2 game, for the Nokia N-Gage, a unique phone-game console hybrid with a button-like joystick. Its shape—a rectangle with one long rounded side at the bottom—earned it the nickname “taco phone.” Red Faction did something new for mobile games in 2003: It was the first fully 3D cell phone game with deathmatch played over Bluetooth. Up to three phones in the same room could deathmatch head-to-head. Looking back, I only wish this innovation had been on a platform that had more players! We were proud of our work, though.

To read the rest of this chapter and the full autobiography, head to your nearest bookstore or online emporium of literature and order Doom Guy: Life in First Person by John Romero (Abrams Press, £21.99). It’s out Thursday, 20th July. Thanks to John and Brenda Romero and Georgie Kenny of Abrams & Chronicle Books.

Remember to read our interview with John Romero, where he looks back on the technical achievements of his career and shares his experience of writing the book. There's more information there about the mobile multiplayer breakthroughs of Red Faction.