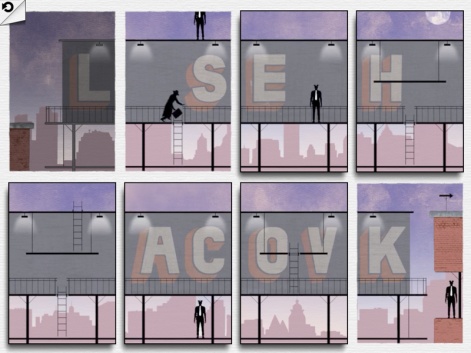

Stories are often similar in their construction; like panels of a comic book, they unfold in the same direction, from the beginning to end, left to right, top to bottom.

Framed dares to experiment with these conventions.

What would happen if you switched the last panel in a page with the first? Would the hero still survive the tale if events played out in a different order?

Shifting panels

The formation of Loveshack, a now multi award-winning independent studio based in Melbourne, Australia, is a more familiar story.

Made up of a small group of industry veterans - Joshua Boggs, Ollie Browne and Adrian Moore - after meeting at another studio (Firemint, since bought by EA), the colleagues decided to see what they could create on their own, in their own studio.

Framed, the team's first project, took two years to complete, with the team size expanding throughout development. By the end, Framed had other names working on it besides the studio founders, including Zoe Quinn, Ben Weatherall, Josh Bradbury and Ben Boersch.

Sliding puzzle

Joshua Boggs explains that Framed started life as a thought experiment.

"Rather than play with a set of actions as you normally would in a game - run, jump, shoot - we asked: what would happen if you played with the context in which an action happened instead?

"We played with this idea for a while, and it resulted in some pretty interesting scenarios, but they didn't play very well. So we focused on making the scenes as readable as possible.

"This meant making sure the character is always running from left to right and keeping the scenarios simple enough so that they could be understood without any words."

What would happen if you played with the context in which an action happened?

It's a strong concept, with the player sliding around panels of a living comic book as its lead character darts between them, performing different actions depending on how he (or she) enters the frame.

Simplicity by design and gameplay, also backed with a striking aesthetic, this ethos carried into the prototyping phase.

"We're big fans of paper prototyping," Boggs says.

"[All] of our level design is done on paper before we touch computers. Once we start creating the actual content, we use a lot of Photoshop for the art, 3ds max and Premiere for the 3D models and animation, and we used Reason for the audio engineering."

The game's animation, which many believe is rotoscoped, was key-framed by Stuart Lloyd, with the characters being rigged 3D models that animate over Browne's drawn backgrounds.

Frame it

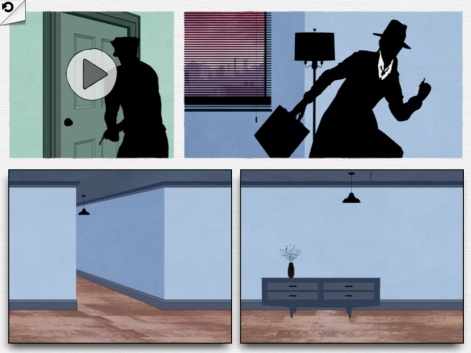

The game's striking minimalist style and noir tone was decided on because it felt like a natural fit for the concept, with some of the prototype created in purist black and white.

Ollie Browne explains: "Our very first gameplay test - which you can still see on YouTube (see below) - had some basic colour, but the next five-scene playable prototype we made was completely greyscale, all dingy greys and blacks with splashes of red for blood.

"It made sense from a noir point of view, but it was a little bit depressing.

"From there, as I added more and more colour to the backgrounds, I found it offset the silhouetted characters really nicely, as well as made the game pop a lot more on smaller screens. Also, I felt that cool pastel colours really fit the 'retro' tone of the setting as well as [making] the game stand out."

He says the reason he decided on the silhouetted characters was so players would be able to project their own interpretation and motivations onto the characters.

While it needed to have that gritty noir feel, Framed also needed to be playful and fun.Ollie Browne

"As soon as game characters have a face, their expressions become much more readable and obvious, and it takes away from the central mystery," Browne says.

This approach also extends to the fact that, mechanically, the player need to be able to see what the character is doing. A black silhouette over a colourful background makes everything much clearer.

Fantastical reality

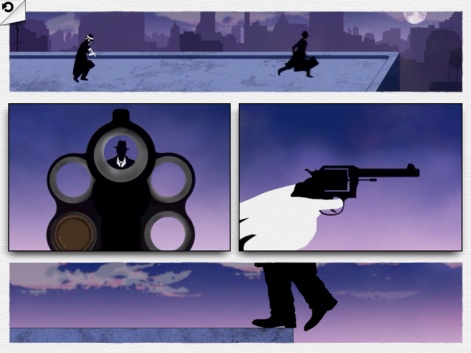

In part, the visual style was also inspired by Hollywood graphic designer Saul Bass, especially his title work for Hitchcock, although Browne was careful to not mimic the style too closely.

To avoid this, he went for more realistically proportioned character designs superimposed over backgrounds splashed in the cool colours of that era.

"I felt Framed needed to be more 'fantastical reality' than just 'fantastical', and while it needed to have that gritty noir feel, it also needed to be playful and fun," continues Browne.

"I looked at lot of comics from the era, too. They use a lot of the same colours, which are in some ways the result of the way they were inked and printed."

Other inspirations were the games of Browne's childhood: Strider, ActRaiser and ESWAT: City under Siege. He fondly remembers their "glorious parallaxed backdrops of distant mountains and cities" and wanted Framed to capture some of that same epic feeling, making sure many of the scenarios had a distant horizon, adding a peripheral story to the world and setting.

"On top of that, we are all certainly are big fans of film noir in general," says Browne.

"What was important was to take these inspirations and make something new from their parts while adding my own stylistic leanings, which hopefully is what we achieved," Browne muses.

Silent movies

As the game's story is portrayed through this striking visual style, it was important that the soundtrack matched the action on-screen. The lack of traditional sound effects and character voices made this doubly important.

"From the start I approached it as a purely musical project," Adrian Moore, designer and composer at Loveshack reveals.

"I felt that it would be fun to have the game be scored like a movie, where what is happening on screen is punctuated with a suitable mood - no traditional sound effects allowed."

Development of the music started alongside the art, animation and design.

"I started with some really experimental sounds - some heavy scratchy guitar, a lot of really futuristic and radical-sounding, very bold samples. The mood was quite dark," Moore says.

I spent about a month full-time mixing the soundtrack to get it all sounding right.Adrian Moore

"It never really sounded right so I started to bring it back to something more contemporary; attempting to create something more 'classic noir' but with a modern twist.

"Once I was getting happy with a general style I went through a phase of writing two separate pieces of music for each scene - one for when the scene is won and another for when the scene is failed.

"Literally every last footstep was timed to the music."

However, it soon became clear that not only was this approach going to require a huge amount of music but that players would be able to use the music as cues for winning and losing, effectively meaning they could play the game with their eyes closed.

For this reason, the team settled on spreading a single backing track over multiple scenes, with each character having their own recognisable theme.

Added punch

Towards the end of the project, Moore says he decided the purely electronic music - which was written in Reason - should be lifted with some live performances, "especially the saxophone parts in the jazz music".

Lauren Mullarvey - "an insanely talented sax player" - was recorded live in the Loveshack office, while Jay Scarlett overdubbed live trumpets and trombones, and Sam Izzo added keyboard parts.

"I spent about a month full-time mixing the soundtrack to get it all sounding right, including versions of each track featuring mostly just drums - so that when the game is waiting for the players' turn, the fullness drops out as if to provide a bit of a break but while keeping the swing going," Moore says.

The final element was the the punctuated in-game moments such as cops bursting through doors and glass smashing. All drum parts, they are triggered separately from the main music so they are in perfect time with the on-screen action.

"The end result is hopefully unique," Browne says. "It's an original score featuring accented moments as the characters in the game do their thing."

Noir tutorial

Just as the game's music developed through experimentation, Loveshack hoped that players of all skill levels would learn the mechanics of Framed organically through play.

Although it nudges the player slightly when new mechanics are introduced, Framed lacks a tutorial in a traditional sense, with Loveshack honing its readability by reacting to feedback from touring festivals.

"For example, the very first level teaches the interaction itself of dragging panels, the next scene teaches you that you can re-arrange the panels to change outcome, and then things slowly get more a more complex in the following level," say Boggs.

"We do this for every new mechanic."

In this way, he says the game feels reactive to whatever the player is doing as a form of subconscious affirmation.

"If the player ever tried to do things that they couldn't actually do, we would deliberately not give any feedback to discourage the behaviour," he states.

"We're drawn to repeat actions that we get positive feedback and affirmation from, so we took advantage of human psychology to teach players their boundaries."

A twist

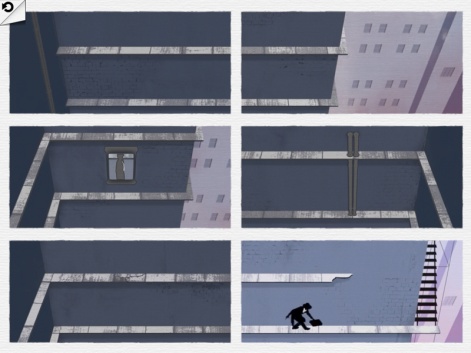

Keeping the tutorial in line with the pure design of the rest of the game, the complexity of Framed comes from the puzzles themselves.

"While you're just re-arranging panels, it's the implications of those changes which have subtle knock-on effects throughout the whole scene," Boggs argues.

"One of my favourite levels in the game is the orange/blue walls. At its purest, this scene is a logic-gate puzzle where you're navigating the environment and the direction you're coming from is constantly being altered based on your environment.

It was very important to us that any twist on the mechanic added depth to the game and not just complexity.Joshua Boggs

Layering onto this, the game introduces new mechanics such as allowing panels to be rotated.

"This gets players thinking about how the page layout changes based on changes they make to panels," Boggs says.

"But we made sure that each new mechanic was a natural extension on the core idea. It was very important to us that any twist on the mechanic added depth to the game and not just complexity."

Back to source

Read in this way, the development of Framed appears to be a fairly linear affair. It wasn't.

Loveshack's original idea featured a protagonist who was self-aware within a work of fiction; their only means of escape being to change the order of events.

"The game underwent a few radical changes in terms of how the narrative was presented and delivered," remembers Boggs.

"At one point we were experimenting with a much shorter narrative which you had to repeat in different orders, so that you were discovering new information with each play-through.

"We ultimately decided not to go down that route however, as it added a lot more complexity to a very carefully-designed and minimal game."

Evenso, as development progressing keeping to the core of tight, minimalist style combined with fresh and open gameplay was complex enough.

"Some of the most interesting things we discovered during development were simply unsustainable given prior choices we had made in the game's design," says Boggs.

"For example, my favourite things are the levels where you're actually changing how the same action can be interpreted.

"These were great to make, but inevitably had to be simple and restrictive. We wanted to make sure that we didn't waste people's time, so every scenario in the game is exploring a unique twist from a design perspective. We didn't want to rehash the same puzzles or content for the sake of game length."

Fixed point

Like the panels it's made of, Framed shifted and changed over the course of its development, adapting to feedback and the results of experimentation.

We're refusing to take part in the race to the bottom, and that allows us to define success on our own terms.Joshua Boggs

One decision came easy, however - Framed was always been planned as a paid iOS game ($4.99).

"The App Store has grown and matured to the point that you don't really need to make a game [that appeals to] everyone to succeed," Boggs says.

"By making the games that we want to play, we're refusing to take part in the race to the bottom, and that allows us to define success on our own terms, and to choose a price that fits our game, rather than making a game that fits a particular monetisation strategy.

"When there are thriving niches that are less risky than competing in the race to the bottom; and when these thriving niches give you the opportunities to make the games you want to make, why would we consider going free?"

It's a compelling argument for the premium model and just like Framed, it's an interesting take on something a lot of people are passionate about.

The release of Framed doesn't mark the last panel in the comic strip of Loveshack's existence, though, and we're sure to see more from this exciting young studio in the future.

Loveshack is already exploring what the follow-up to Framed will be and is working away on porting Framed to other platforms.

In the words of Boggs: "2015 is going to be pretty exciting."